Last weekend, a few days before I turned 59, I went for a walk around Walden Pond. My wife was away for the weekend and it was sunny-autumn-crisp out and I was being a total slug on the couch, watching old episodes of M*A*S*H, so, what the hell, I drove west to Concord and circumabulated the pond that Henry David Thoreau made famous in his 1854 book Walden, or Life in the Woods. It was uncrowded. A few strollers strolled and a gaggle of giggling Chinese students, wait for cliche, took photos of everything. Two fishermen, still as logs, floated in row boats. A swimmer in a wet suit churned across the pond, bisecting it the long way. The trees' leaves had turned weeks ago, but some retained hints of dying color, and the water's flat surface winked like a blue diamond. My counter-clockwise jaunt included a stop at the site of Thoreau's cabin, long ago dismantled. As per tradition, in homage to the writer/recluse I tossed a stone on a pile of millions of stones sinking into the resistant earth.

About a half mile from the cabin, in Thoreau's time, a train had rattled by now and then. All that infernal locomotion got him thinking: "We do not ride on the railroad; it rides upon us." 2019 update: "We do not use the Internet; it uses us." Thoreau also advised us to simplify: "Keep your accounts on your thumb nail." 2019 update: "Get offline, already."

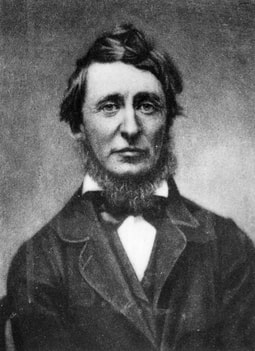

Near the parking lot at Walden Pond there's a new visitor center powered entirely by a rack of solar panels. Here I was reminded that Thoreau succumbed to consumption. In old-timey speak that means he died of TB -- a very writerly demise. Perhaps staring at a blank piece of paper inhibits the immune system. I also realized that Thoreau was only in his late 20s when he stayed for two years alone at the pond. Somehow, I thought he was older. Perhaps because his photos make him look aged; or perhaps because it's hard to imagine a young man having the patience and fortitude he exhibited. Thoreau kept meticulous logs of flora and fauna at the pond, which are now used by Boston University Professor Richard Primack to pinpoint the degree to which spring comes weeks earlier to Walden Pond than it did in the 1840s. The quickening spring, caused by climate change, has produced a cascade of problems for birds, bugs and flowers -- details are available in this short NPR radio report.

About a half mile from the cabin, in Thoreau's time, a train had rattled by now and then. All that infernal locomotion got him thinking: "We do not ride on the railroad; it rides upon us." 2019 update: "We do not use the Internet; it uses us." Thoreau also advised us to simplify: "Keep your accounts on your thumb nail." 2019 update: "Get offline, already."

Near the parking lot at Walden Pond there's a new visitor center powered entirely by a rack of solar panels. Here I was reminded that Thoreau succumbed to consumption. In old-timey speak that means he died of TB -- a very writerly demise. Perhaps staring at a blank piece of paper inhibits the immune system. I also realized that Thoreau was only in his late 20s when he stayed for two years alone at the pond. Somehow, I thought he was older. Perhaps because his photos make him look aged; or perhaps because it's hard to imagine a young man having the patience and fortitude he exhibited. Thoreau kept meticulous logs of flora and fauna at the pond, which are now used by Boston University Professor Richard Primack to pinpoint the degree to which spring comes weeks earlier to Walden Pond than it did in the 1840s. The quickening spring, caused by climate change, has produced a cascade of problems for birds, bugs and flowers -- details are available in this short NPR radio report.

Something stuck with me, the other day at the pond. I stopped on a rise above the main beach, a grassy area among several towering red oaks. Acorns crunched underfoot. The wind picked up and I stood beneath one of the trees as dozens of leaves freed themselves from the tips of branches yawning 40, 50 yards above my head, and down the reddish-brown leaves floated, twirling down, down, down. Suddenly I recalled doing this as a child, in the 1960s: standing under a tall tree as a wind-gifted flurry of leaves fell toward me. Then, as now, I wanted to grab a leaf before it hit the ground; to accomplish this goal, then as now, I settled on two techniques. One: pick out a single leaf and race about in pursuit, following its zigzagging, wind-whipped chaotic path. Not easy, for a nimble kid. Absurd, for a gimpy semi-oldster. Two: just stand there and wait, hand outstretched. Sooner or later, a leaf will come to you. As a kid, of course, I could never wait long enough for this miracle to occur. As an adult, the same.

In 2019, on the cusp of my 60th year, I tried to catch a spinning, falling leaf and failed -- at first. Then I faked left, ducked right, jumped up and, snatch, got one! I brought it home, took its photo. Now you might say that the best way to catch a falling leaf is to pick it off the ground after it finishes falling...yes, you're right, but you don't get it. Then it's not falling anymore. And here's where I assert that addressing climate change is like standing in wind under an old-uncle red oak that's stubbornly, generously shedding its leaves, and the wind is time and the leaves are policy ideas, or people, or maybe greenhouse gases, and the leaf-catcher symbolizes our crazy world overwhelmed by...

In 2019, on the cusp of my 60th year, I tried to catch a spinning, falling leaf and failed -- at first. Then I faked left, ducked right, jumped up and, snatch, got one! I brought it home, took its photo. Now you might say that the best way to catch a falling leaf is to pick it off the ground after it finishes falling...yes, you're right, but you don't get it. Then it's not falling anymore. And here's where I assert that addressing climate change is like standing in wind under an old-uncle red oak that's stubbornly, generously shedding its leaves, and the wind is time and the leaves are policy ideas, or people, or maybe greenhouse gases, and the leaf-catcher symbolizes our crazy world overwhelmed by...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed