Consider this, please

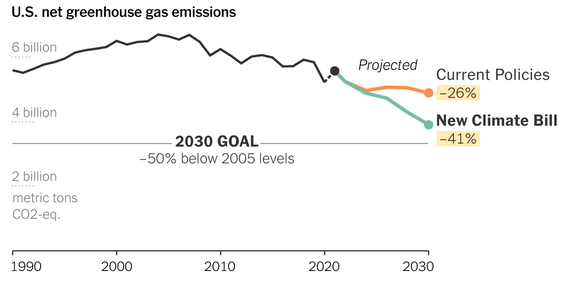

There’s a country that contains about four percent of the world's population. Its people live pretty well, on average, and account for roughly 13 percent of global emissions of carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas (GHG) that's primarily responsible for climate change. (We're not accounting for the carbon footprint of the imported goods they consume.) So, in 2022, this country's government passed legislation that, according to models, would reduce its GHG emissions a whopping 40 percent by 2030 – that is, compared to the peak level emitted in 2005. They’d already made it halfway to the 40 percent goal over the past 17 years, taking advantage of low-hanging-fruit solutions such as higher gas mileage standards for vehicles and the adoption of LED lighting, and now they're ready to achieve the remaining reductions in only eight years. Climate change is an existential crisis, the nation's leaders proclaim. Future generations will judge us sternly if we don't take decisive action.

There’s a country that contains about four percent of the world's population. Its people live pretty well, on average, and account for roughly 13 percent of global emissions of carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas (GHG) that's primarily responsible for climate change. (We're not accounting for the carbon footprint of the imported goods they consume.) So, in 2022, this country's government passed legislation that, according to models, would reduce its GHG emissions a whopping 40 percent by 2030 – that is, compared to the peak level emitted in 2005. They’d already made it halfway to the 40 percent goal over the past 17 years, taking advantage of low-hanging-fruit solutions such as higher gas mileage standards for vehicles and the adoption of LED lighting, and now they're ready to achieve the remaining reductions in only eight years. Climate change is an existential crisis, the nation's leaders proclaim. Future generations will judge us sternly if we don't take decisive action.

The company went bankrupt in 1979 and its owner spent seven years in prison for fraud.

The company went bankrupt in 1979 and its owner spent seven years in prison for fraud. For social, political and economic reasons too numerous and, frankly, boring to enumerate, the new climate legislation – inanely dubbed the Inflation Reduction Act – depends almost entirely on subsidies. There are no carbon taxes, which would dissuade people and corporations from burning the fossil fuels that produce GHG emissions. Instead, a great, green giveaway has been instituted: tax breaks and tax rebates and hundreds of billions in federal funding for all things clean and renewable. It's like those wacky 1970s TV commercials for the discount electronics store Crazy Eddie, but now it's Crazy Green Eddie and the prices are INSAAANE! Well, not quite, but maybe low enough to make your average Joe and Josephina consider an electric car and solar panels.

Katy -- aka, Catherine Douglass, lady-in-waiting -- failed to prevent the assassination of King James I in 1437. Her arm was broken.

Katy -- aka, Catherine Douglass, lady-in-waiting -- failed to prevent the assassination of King James I in 1437. Her arm was broken. This plucky country – yes, it's our United States of America – is now running a very big experiment. Can we achieve such a massive undertaking, a revolution within our energy sector, with a painless all-carrot and no-stick approach? And will this strategy become a workable template for other countries? Some say yes, some say no, some say it depends. Others point out that it's a planetary problem requiring a planetary solution, and that we should, once more, get over ourselves. But, at any rate, the deed is done. There will be no new U.S. climate legislation for a while, so it's wait and see.

But wait for how long? If our green gambit isn't producing the 2.5 percent per year reduction in GHG emissions that models project, at some point we'll need to unleash the stick alongside the carrot. We'll need to levy taxes and fees to raise the price of behaviors that propel climate change. So, when exactly do we admit failure – a hard thing to do, in politics and life – and adopt stronger steps to help keep global temperature increases in the industrial era below 2.5 or 2 degrees Celsius? (Temps are currently at 1.2 degrees above pre-industrial levels and soaring; sorry, the 1.5 degree goal is utter fantasy.)

Of course, we have to give the legislation a little time, a fair chance to succeed. On the other hand, we can't go all the way to 2030 if yearly reductions are lacking. Yes, there may be a learning curve, a period of adjustment, and yes, technocrats will always urge a tweak to this subsidy and a twerk to that rebate, but the Earth's physical systems don't care one fig for our flailings. There's too much at stake to be prideful. If this "really big green sale" attempt at lessening our contribution to a gathering global disaster isn't sufficient – and, alas, it probably won’t be – then we have to be brave enough to admit it.

So, I say, let's give it three years and a few months. It'll be the spring of 2026, with mid-term elections on the horizon. There's a decent chance that Congress and the presidency will be controlled by Democrats. At that juncture, we may be gifted one last, blessed chance to get serious, really serious about climate change. Now, if denialist Republicans are in control, it's "Katy bar the door!" and let's hope the rest of the world are doing better than us.

But wait for how long? If our green gambit isn't producing the 2.5 percent per year reduction in GHG emissions that models project, at some point we'll need to unleash the stick alongside the carrot. We'll need to levy taxes and fees to raise the price of behaviors that propel climate change. So, when exactly do we admit failure – a hard thing to do, in politics and life – and adopt stronger steps to help keep global temperature increases in the industrial era below 2.5 or 2 degrees Celsius? (Temps are currently at 1.2 degrees above pre-industrial levels and soaring; sorry, the 1.5 degree goal is utter fantasy.)

Of course, we have to give the legislation a little time, a fair chance to succeed. On the other hand, we can't go all the way to 2030 if yearly reductions are lacking. Yes, there may be a learning curve, a period of adjustment, and yes, technocrats will always urge a tweak to this subsidy and a twerk to that rebate, but the Earth's physical systems don't care one fig for our flailings. There's too much at stake to be prideful. If this "really big green sale" attempt at lessening our contribution to a gathering global disaster isn't sufficient – and, alas, it probably won’t be – then we have to be brave enough to admit it.

So, I say, let's give it three years and a few months. It'll be the spring of 2026, with mid-term elections on the horizon. There's a decent chance that Congress and the presidency will be controlled by Democrats. At that juncture, we may be gifted one last, blessed chance to get serious, really serious about climate change. Now, if denialist Republicans are in control, it's "Katy bar the door!" and let's hope the rest of the world are doing better than us.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed