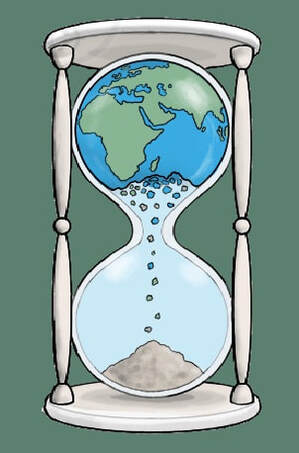

A fascinating academic paper was published seven years ago this August -- it took that long for it to reach my wandering attention -- regarding the time lag between an emission of carbon dioxide and the maximum amount of warming caused by that emission. The paper, by Katherine L. Ricke and Ken Caldeira, gives the answer away in the title: Maximum Warming Occurs About One Decade After A Carbon Dioxide Emission.

What's with the time delay? It has something to do with uncertainties related to the carbon cycle, climate sensitivity and thermal inertia. More specifically, with the uptake of CO2 by the oceans and biosphere, with radiative forcing and feedbacks and heat exchange and, oh, just read the paper and pretend you understand it.

So, ten years. From a geological perspective, that's nothing. It might as well be instantaneous, like a punch -- pow! -- and the resulting pain -- ow! But from the perspective of a human life, a ten-year gap is a significant cause and delayed full effect. A case of crime and gradual punishment. After all, air pollution can travel from tailpipe to bronchial sac in a matter of minutes, and water pollution can destroy a duck within days. Radiation from a nuclear explosion takes between a few hours and several years to kill a human being, depending on proximity and potency. Now think of how we talk to each other. An angry word can injure instantly and then fade away. Or it might fester, poisoning a relationship. A loving word or caress, applied at the right moment, can last a lifetime.

Let's take your typical U.S. citizen, one who claims to be concerned about climate change. What might she guess about the time lag between emissions cause and warming effect? Every morning she starts up her fossil-fueled death mobile (kidding, sorta) and when, exactly, do those ejected CO2 molecules wreck full havoc? I'm guessing that most people imagine the effect as fairly immediate -- a few days or weeks maybe for the gaseous gunk to fly up and meet its chemical destiny, but certainly not a gradual process taking ten years.

But that's all speculation. And what does it really matter?

It matters because matters of timing may influence public attitudes and the enactment of policies to address climate change. For instance, the realization that today's climate mayhem -- heat waves, wildfires, melting glaciers, souped-up storms, and so on -- is a function of yesteryear's emissions, that everything we've spewed since, say, the Year We Elected Trump has yet to come due -- well, isn't that a bracing thought? Might that spur action? On the other hand, if we believe that today's emissions won't reach maximum warming power for forty years -- a position once held by many scientists -- then the temptation might be not to worry so much about such a distant threat and, besides, someone's bound to invent a super CO2-sucking machine by then.

What's with the time delay? It has something to do with uncertainties related to the carbon cycle, climate sensitivity and thermal inertia. More specifically, with the uptake of CO2 by the oceans and biosphere, with radiative forcing and feedbacks and heat exchange and, oh, just read the paper and pretend you understand it.

So, ten years. From a geological perspective, that's nothing. It might as well be instantaneous, like a punch -- pow! -- and the resulting pain -- ow! But from the perspective of a human life, a ten-year gap is a significant cause and delayed full effect. A case of crime and gradual punishment. After all, air pollution can travel from tailpipe to bronchial sac in a matter of minutes, and water pollution can destroy a duck within days. Radiation from a nuclear explosion takes between a few hours and several years to kill a human being, depending on proximity and potency. Now think of how we talk to each other. An angry word can injure instantly and then fade away. Or it might fester, poisoning a relationship. A loving word or caress, applied at the right moment, can last a lifetime.

Let's take your typical U.S. citizen, one who claims to be concerned about climate change. What might she guess about the time lag between emissions cause and warming effect? Every morning she starts up her fossil-fueled death mobile (kidding, sorta) and when, exactly, do those ejected CO2 molecules wreck full havoc? I'm guessing that most people imagine the effect as fairly immediate -- a few days or weeks maybe for the gaseous gunk to fly up and meet its chemical destiny, but certainly not a gradual process taking ten years.

But that's all speculation. And what does it really matter?

It matters because matters of timing may influence public attitudes and the enactment of policies to address climate change. For instance, the realization that today's climate mayhem -- heat waves, wildfires, melting glaciers, souped-up storms, and so on -- is a function of yesteryear's emissions, that everything we've spewed since, say, the Year We Elected Trump has yet to come due -- well, isn't that a bracing thought? Might that spur action? On the other hand, if we believe that today's emissions won't reach maximum warming power for forty years -- a position once held by many scientists -- then the temptation might be not to worry so much about such a distant threat and, besides, someone's bound to invent a super CO2-sucking machine by then.

Before proceeding further, let's consider another timing aspect of climate change: how long does carbon dioxide stay in the atmosphere doing its warming thing? A couple of years? No. A decade or two and then it washes out? No again. A century, could it possibly stay up there that long? NO AGAIN. The answer is 300-1,000 years, according to NASA. For historical perspective, a thousand years ago Thorkell the Tall was banished from England, probably because Cnut the Great suffered from little man's syndrome. In 1021 most people's lives were nasty, short and brutish, if they were lucky, and bleeding was considered the standard of care among medical professionals.

Effectively, we're stuck with what we've done. This is hard to grasp and harder to accept. The persistence of climate change runs counter to our lived experience of cause and effect. People expect that if they stop doing something bad, things will get better. So if you stop procrastinating and fix the roof, water will cease leaking into the kitchen. If you reduce salt intake, your blood pressure will go down. If you and fellow citizens cut down on nitrogen oxide emissions by embracing renewable energies, the air will become less smoggy. One more: if you cease buying junk you don't need, you'll probably not go broke. And all this is true -- just not with climate change.

Climate change is not reversible within time frames that are remotely relevant to human civilization. A useful metaphor may be quitting smoking; when a smoker quits, his lungs don't heal over time. He has to live, or die, with the damage done. By this way of thinking, we've scarred the Earth's lungs and humanity will have to deal with the results for scores of generations.

(Kids to parents and grandparents: thanks for screwing us over so royally. Take care of yourself in old age.)

In fact, if in some eco-fantasy the human race suddenly stopped all greenhouse-gas emissions, we'd still get several more years of increasing warming! (See discussion of timing lag at top of blog.) So, it's like this: we can't even declare that when we stop doing something bad, things at least won't get worse!

Yes, it's screwy, FUBAR, a real balagan as the Israelis say. It's positively upside down like those trees that my wife and I recently viewed at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams. Hung by their root-heels in a courtyard of the museum, which in previous lives was both a textile and electronics factory, they nonetheless continue to grow toward the sun and away from the earth. Therefore we are compelled, according to the artist's statement, to redefine the tree not merely as a source of building materials or generator of oxygen or lovely home for birds and squirrels, but as an unstoppable growth-response system.

Similarly, I wonder, in order to face the daunting counter-calculus of climate change, shouldn't we redefine our perspective about ourselves in time and space?

Make of that what you will. My visceral reaction on first beholding the artwork: it seemed a pretty cruel thing to do to a tree. I looked away. A while later we got hungry and went to lunch; the French fries in the MOCA café were awfully good.

Effectively, we're stuck with what we've done. This is hard to grasp and harder to accept. The persistence of climate change runs counter to our lived experience of cause and effect. People expect that if they stop doing something bad, things will get better. So if you stop procrastinating and fix the roof, water will cease leaking into the kitchen. If you reduce salt intake, your blood pressure will go down. If you and fellow citizens cut down on nitrogen oxide emissions by embracing renewable energies, the air will become less smoggy. One more: if you cease buying junk you don't need, you'll probably not go broke. And all this is true -- just not with climate change.

Climate change is not reversible within time frames that are remotely relevant to human civilization. A useful metaphor may be quitting smoking; when a smoker quits, his lungs don't heal over time. He has to live, or die, with the damage done. By this way of thinking, we've scarred the Earth's lungs and humanity will have to deal with the results for scores of generations.

(Kids to parents and grandparents: thanks for screwing us over so royally. Take care of yourself in old age.)

In fact, if in some eco-fantasy the human race suddenly stopped all greenhouse-gas emissions, we'd still get several more years of increasing warming! (See discussion of timing lag at top of blog.) So, it's like this: we can't even declare that when we stop doing something bad, things at least won't get worse!

Yes, it's screwy, FUBAR, a real balagan as the Israelis say. It's positively upside down like those trees that my wife and I recently viewed at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams. Hung by their root-heels in a courtyard of the museum, which in previous lives was both a textile and electronics factory, they nonetheless continue to grow toward the sun and away from the earth. Therefore we are compelled, according to the artist's statement, to redefine the tree not merely as a source of building materials or generator of oxygen or lovely home for birds and squirrels, but as an unstoppable growth-response system.

Similarly, I wonder, in order to face the daunting counter-calculus of climate change, shouldn't we redefine our perspective about ourselves in time and space?

Make of that what you will. My visceral reaction on first beholding the artwork: it seemed a pretty cruel thing to do to a tree. I looked away. A while later we got hungry and went to lunch; the French fries in the MOCA café were awfully good.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed