For all you Cixin Liu fans out there, an English translation of his Supernova Era is finally available. Written in 2004, this bonkers novel about a celestial event that kills everyone on Earth over the age of thirteen is probably not the best place to start reading Liu, the master of Chinese science fiction. (With Stephen King and Haruki Murakami, he ranks as one of the world's most popular and translated authors.) A couple of years ago I began with Liu's epic trilogy, The Three-Body Problem. After catching up on sleep, I next sampled his mind-twisting short stories in The Wandering Earth, gobbled up Ball Lightning and just last week found Supernova Era. This time-reversed consumption of the author's work was a bit like hurtling backwards 13.8 billion years to the Big Bang, when all the craziness, leading to us, began.

But we're not a book-review blog. We're all about climate change here, about hanging in the Anthropocene Era, so make sure not to skip Liu's illuminating Afterword to Supernova Era, written recently. In it, he asserts that "China used to have no sense of the future. In our subconscious, today was the same as yesterday, and tomorrow was going to be the same as today. The future as a concept doesn’t really appear in traditional Chinese culture…But today, ‘futuristic’ is the most salient impression one gets from China. With everything changing at a blinding pace, a breathtaking future rises like the sun from the horizon, fully compelling, yet suffused with terrifying uncertainty and danger…"

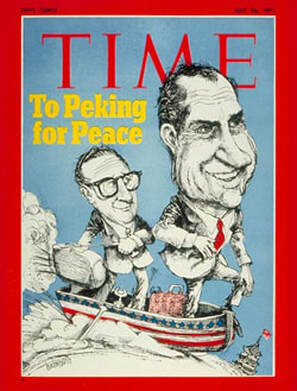

I've never been to China, but it's always fascinated me. As a kid I eagerly followed news about ping-pong diplomacy and Nixon's voyage to meet Mao. A copy of Life magazine with a cover photo of cyclists flowing through Tiananmen Square, every person dressed in identical gray uniforms, sat like a portal to another world on the round, marble coffee table of our suburban Connecticut home. Today, I understand fully that China -- now a nation of automobile drivers and meat eaters, of people buying their first air conditioners -- is the most prolific current emitter of greenhouse gases. What they choose to do in the next several years will greatly determine to what degree climate change wrecks havoc on human civilization.

So what are they going to do?

But we're not a book-review blog. We're all about climate change here, about hanging in the Anthropocene Era, so make sure not to skip Liu's illuminating Afterword to Supernova Era, written recently. In it, he asserts that "China used to have no sense of the future. In our subconscious, today was the same as yesterday, and tomorrow was going to be the same as today. The future as a concept doesn’t really appear in traditional Chinese culture…But today, ‘futuristic’ is the most salient impression one gets from China. With everything changing at a blinding pace, a breathtaking future rises like the sun from the horizon, fully compelling, yet suffused with terrifying uncertainty and danger…"

I've never been to China, but it's always fascinated me. As a kid I eagerly followed news about ping-pong diplomacy and Nixon's voyage to meet Mao. A copy of Life magazine with a cover photo of cyclists flowing through Tiananmen Square, every person dressed in identical gray uniforms, sat like a portal to another world on the round, marble coffee table of our suburban Connecticut home. Today, I understand fully that China -- now a nation of automobile drivers and meat eaters, of people buying their first air conditioners -- is the most prolific current emitter of greenhouse gases. What they choose to do in the next several years will greatly determine to what degree climate change wrecks havoc on human civilization.

So what are they going to do?

Cixin Liu

Cixin Liu I don't know; nobody knows. Maybe China will build hundreds of new coal plants. Or carpet the Gobi Desert with solar panels. So far, it looks like they're doing both. Could they be willing, given new American leadership in 2020, to enter into a climate agreement that's more binding and effective than the Paris Accords? Will President Pete Buttigieg and his two rescue dogs make an epic mission to China that culminates in a World New Green Deal? Or will it be just more superpower ping-pong: back and forth, tit for tat, tariffs up, tariffs down. Hong Kong, Taiwan, perpetual cyber war. And billions of crappy-plastic Happy Meal toys, made in carbon-belching Chinese factories, floating across the Pacific to our grateful shores...

China, which prizes conformity and tradition, is changing at warp-ten speed. Confusion reigns, especially among middle-aged and elderly folks. But the younger generation, writes Liu in his Afterword, "is wholly integrated into this new world as native inhabitants of the information age. They are deft users of the internet with no need for instruction, and have quickly adopted it as an inseparable external organ. To them, this is the way the world ought to be, and change is a matter of course." And yet -- my observation, not Liu's -- China represses free speech and basic human rights. And yet it remains a totalitarian country run by a gang of corrupt old men.

China: dizzying and contradictory, inspiring and depressing all at the same time. Liu, however, has tastier cosmic fish to fry than one burgeoning country. He circles back to mankind's fear of abandonment, a wild emotion that he sees as the ultimate driver of behavior. "Humanity," he states, "is an orphan unable to find its parents’ hands." If this is so, perhaps it's time we stop looking up at fading icons or down glumly at our feet or with catatonic rigor at our omnipresent screens,. Rather, maybe we should look to the sides, to the flailing hands of our brothers and sisters, here and across the seas, as we like it or not step together into the breathtaking future.

China, which prizes conformity and tradition, is changing at warp-ten speed. Confusion reigns, especially among middle-aged and elderly folks. But the younger generation, writes Liu in his Afterword, "is wholly integrated into this new world as native inhabitants of the information age. They are deft users of the internet with no need for instruction, and have quickly adopted it as an inseparable external organ. To them, this is the way the world ought to be, and change is a matter of course." And yet -- my observation, not Liu's -- China represses free speech and basic human rights. And yet it remains a totalitarian country run by a gang of corrupt old men.

China: dizzying and contradictory, inspiring and depressing all at the same time. Liu, however, has tastier cosmic fish to fry than one burgeoning country. He circles back to mankind's fear of abandonment, a wild emotion that he sees as the ultimate driver of behavior. "Humanity," he states, "is an orphan unable to find its parents’ hands." If this is so, perhaps it's time we stop looking up at fading icons or down glumly at our feet or with catatonic rigor at our omnipresent screens,. Rather, maybe we should look to the sides, to the flailing hands of our brothers and sisters, here and across the seas, as we like it or not step together into the breathtaking future.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed