Today, which is the first day of autumn, feels like the last day of summer. Just a few, scrappy clouds pester the sky and the temperature has risen to the mid-60s by mid-morning. The forest around Mount Monadnock is deep green, not yet acquiring the browns and golds of yearly ruin. Today is also Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, and maybe I should be shuttered in shul or home fasting, maybe I should be sitting on my porch contemplating inscrutable sparrows and reviewing my sins, which, by the way, is hard to do while fasting but that’s probably intended. Instead I’ve had my coffee and donut and driven to my monthly temple, Mount Monadnock, where I make teshuvah, repentance, by turning away from civilization and going up the trail.

Psalm 121, also called a Song for Ascents, begins with an apt question: I lift up my eyes to the mountains – where does my help come from? Put it another way: if standing at the foot of a mountain doesn’t impart some humility, doesn’t cause you to take a deep breath, regret your stubbornness and pledge to be more open to change, then what the heck does?

But first, in the parking lot, I watch a fit young woman with her toddler boy. (You can tell they’re mommy-son by the relaxed way he grabs for her hand.) Nearby sits an elaborate child carrier with padded aluminum frame – the Osprey Poco model, $200. With diapers, wipes, water, snacks, sippy cups, stuffed friends, first aid kit, toddler and child carrier, she’ll probably have 35 squirming pounds on her back. This mom must really be tired of dragging junior to the playground. She must really miss going up.

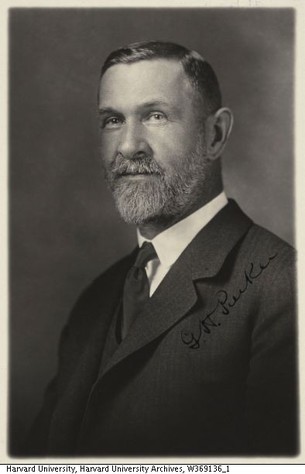

I head due west for a half mile on the Parker Trail – who’s this Parker fellow? The next day I do a little Googling and regret it. Turns out the Parker Trail was cut in 1911 by a Harvard zoologist, George Howard Parker, renowned for “discoveries about the sensory reactions of fishes and the lower invertebrates” – so says The Harvard Crimson. But it’s not his work with earthworms that bugs me; it’s his belief in the coldhearted discipline of eugenics, demonstrated in his article “The Eugenics Movement as a Public Service” in the journal Science (1915). Soberly, Dr. Parker warns against the “defective classes” whose “very growth threatens our civilization with future submergence, if not annihilation.” The solution? Sterilize handicapped people, including the blind and the deaf, in order to improve human “breeding stock.”

Two falls ago, right here, I watched deaf students happily unload from a bus and take this trail named for the man who wanted them neutered.

The definition of “defective classes,” of course, is easily expandable. The Nazis realized this and built their ideology of human destruction in part from the ideals of eugenics. Worth noting on this High Holiday. G. H. Parker lived until 1955 and I wonder if he repented his views after the grisly abominations of the Holocaust, if just in his heart. Probably not – he was an esteemed Harvard professor, after all. Not the humble type. Perhaps we should do penance for him – and for ourselves, for continuing to devalue outsider, suffering groups – by at least renaming this trail. The Freedom Trail is taken. Anyone have a good idea?

Psalm 121, also called a Song for Ascents, begins with an apt question: I lift up my eyes to the mountains – where does my help come from? Put it another way: if standing at the foot of a mountain doesn’t impart some humility, doesn’t cause you to take a deep breath, regret your stubbornness and pledge to be more open to change, then what the heck does?

But first, in the parking lot, I watch a fit young woman with her toddler boy. (You can tell they’re mommy-son by the relaxed way he grabs for her hand.) Nearby sits an elaborate child carrier with padded aluminum frame – the Osprey Poco model, $200. With diapers, wipes, water, snacks, sippy cups, stuffed friends, first aid kit, toddler and child carrier, she’ll probably have 35 squirming pounds on her back. This mom must really be tired of dragging junior to the playground. She must really miss going up.

I head due west for a half mile on the Parker Trail – who’s this Parker fellow? The next day I do a little Googling and regret it. Turns out the Parker Trail was cut in 1911 by a Harvard zoologist, George Howard Parker, renowned for “discoveries about the sensory reactions of fishes and the lower invertebrates” – so says The Harvard Crimson. But it’s not his work with earthworms that bugs me; it’s his belief in the coldhearted discipline of eugenics, demonstrated in his article “The Eugenics Movement as a Public Service” in the journal Science (1915). Soberly, Dr. Parker warns against the “defective classes” whose “very growth threatens our civilization with future submergence, if not annihilation.” The solution? Sterilize handicapped people, including the blind and the deaf, in order to improve human “breeding stock.”

Two falls ago, right here, I watched deaf students happily unload from a bus and take this trail named for the man who wanted them neutered.

The definition of “defective classes,” of course, is easily expandable. The Nazis realized this and built their ideology of human destruction in part from the ideals of eugenics. Worth noting on this High Holiday. G. H. Parker lived until 1955 and I wonder if he repented his views after the grisly abominations of the Holocaust, if just in his heart. Probably not – he was an esteemed Harvard professor, after all. Not the humble type. Perhaps we should do penance for him – and for ourselves, for continuing to devalue outsider, suffering groups – by at least renaming this trail. The Freedom Trail is taken. Anyone have a good idea?

An old stone wall appears and I head north on the Lost Farm Trail. The hardwoods – beech, oak, scraggly-barked maple – have grown tall, so that farm must have been lost a long time ago. I feel strong today and set a fast pace, climbing over mid-sized boulders, implanted stone steps and roots protruding like a teenager’s knees. As the trail gets steeper, the wall fritters itself away, and at the junction to the Cliff Walk I stop to hydrate and munch trail mix. My perch is a rounded loaf of granite with a clear view to the south. The deep-green expanse goes for miles and miles and miles, broken only by blue, watery splotches and large buildings in clearings.

I pick out the Bible Conference facility, built as a farmhouse in 1801 and christened The Ark for its huge size. Later it became an inn frequented by vacationing Monadnock lovers, including a certain Harvard professor. The July 11, 1952 issue of the Jaffrey Recorder and Monadnock Breeze contains an article about the guest register for The Ark in the summer of 1897. “Dr. and Madame George Howard Parker,” we learn, stayed for two and a half weeks and ran up a bill of $30.51, including room and board, use of hats ($1), a ride to Monadnock (76 cents) and a gallon of maple syrup ($1).

Three questions. One, they couldn't bring their own hats? Two, they couldn’t walk to the mountain? Three, a buck for a gallon of maple syrup? A dollar in 1897 was worth 27 smackers today, so that’s still an excellent deal. In 2015 a gallon of grade B maple syrup goes for $55 on amazon.com. Maybe Parker got a special deal from The Ark’s sugar house for being such a muckety-muck. As for hoofing it to Monadnock, in subsequent summers the professor and the owner of the Ark, Joel Poole, together blazed a trail from the inn to what is now the current headquarters of Monadnock State Park, where the great majority of hikers decamp for trips up the White Cross and White Dot trails. In 1921 Poole built an auto road across his land to those trailheads and gave it to the state in memory of his son, Arthur, who died of pneumonia.

That road donation greatly improved access, opening up the mountain to the uncouth, unperfumed masses. Yes, the “defective classes” wanted their share of hiking fun and within decades Monadnock ceased to be a playground for wealthy and privileged Bostonians faux-roughing it at rustic hotels. The Halfway House, a prime destination for elites on the western flank of the mountain, burned down in 1954. The Ark stayed open until 1965, presumably still renting hats.

I pick out the Bible Conference facility, built as a farmhouse in 1801 and christened The Ark for its huge size. Later it became an inn frequented by vacationing Monadnock lovers, including a certain Harvard professor. The July 11, 1952 issue of the Jaffrey Recorder and Monadnock Breeze contains an article about the guest register for The Ark in the summer of 1897. “Dr. and Madame George Howard Parker,” we learn, stayed for two and a half weeks and ran up a bill of $30.51, including room and board, use of hats ($1), a ride to Monadnock (76 cents) and a gallon of maple syrup ($1).

Three questions. One, they couldn't bring their own hats? Two, they couldn’t walk to the mountain? Three, a buck for a gallon of maple syrup? A dollar in 1897 was worth 27 smackers today, so that’s still an excellent deal. In 2015 a gallon of grade B maple syrup goes for $55 on amazon.com. Maybe Parker got a special deal from The Ark’s sugar house for being such a muckety-muck. As for hoofing it to Monadnock, in subsequent summers the professor and the owner of the Ark, Joel Poole, together blazed a trail from the inn to what is now the current headquarters of Monadnock State Park, where the great majority of hikers decamp for trips up the White Cross and White Dot trails. In 1921 Poole built an auto road across his land to those trailheads and gave it to the state in memory of his son, Arthur, who died of pneumonia.

That road donation greatly improved access, opening up the mountain to the uncouth, unperfumed masses. Yes, the “defective classes” wanted their share of hiking fun and within decades Monadnock ceased to be a playground for wealthy and privileged Bostonians faux-roughing it at rustic hotels. The Halfway House, a prime destination for elites on the western flank of the mountain, burned down in 1954. The Ark stayed open until 1965, presumably still renting hats.

A hawk caws. I watch it float, high on a thermal. Its wings barely move. A second hawk appears and they circle about each other, as if tethered. A fluttery wind plays across my granite seat and traffic murmurs far away. As I rest my bones, I notice faint touches of autumn amid the green. Maybe two percent of the tree cover has turned shades of red, yellow and brown. No, make that five percent. Actually, the longer I sit and look out, the more fall emerges, as if it’s progressing before my eyes…make that seven percent.

Oy, better get going before winter comes. I head up the Cliff Walk, which I traversed last month, and it’s drier this time and seems easier going. Are my spirits higher today? Is my old body having a random good day? I pause on Thoreau’s Seat and at Bald Rock and then cross onto the Smith Connecting Trail. The peak of Monadnock, suddenly, rears into view in all its beckoning solitude. Smith’s trail dips through a strip of thick woods and soon I’m climbing above tree line across slabs of granite with veins of white quartz like coagulated stone. On the White Cross Trail I meet my first fellow hikers of the day, a middle-aged woman guiding six spindly, string-bean boys, maybe nine or ten years old. She totes a pack bursting with lunches; the bean-boys bustle and bumble about her like squirrels. Squirrelly bean boys.

One actually says, “Are we there yet?” Two babble nonsense about “marry-ja-wanna” and heroin. Another: “It feels like I’m in an airplane” Still another climbs up the side of a big cairn, constructed over years from hundreds of stones, and he’s got a rock in one hand and clearly intends to cherry-plant it. “No, no,” chides the woman, “that’s not safe.” He backs off and I jump in: “It’s bad karma to touch a cairn,” I instruct, “very bad luck.” Bean-boy behind me: “Really?” “Absolutely,” I continue, “very bad juju,” and now I’m the eight-foot-tall juju dude they’ll laugh about in the cafeteria tomorrow. “I don’t care because I don’t believe in that stuff,” states the thwarted climber. “I do,” asserts his companion because he really does or really wants to or can’t stop himself from saying night if the kid with the rock says day. Meanwhile, the poor woman-in-charge stares at me, hands on hips. I head up the trail.

Oy, better get going before winter comes. I head up the Cliff Walk, which I traversed last month, and it’s drier this time and seems easier going. Are my spirits higher today? Is my old body having a random good day? I pause on Thoreau’s Seat and at Bald Rock and then cross onto the Smith Connecting Trail. The peak of Monadnock, suddenly, rears into view in all its beckoning solitude. Smith’s trail dips through a strip of thick woods and soon I’m climbing above tree line across slabs of granite with veins of white quartz like coagulated stone. On the White Cross Trail I meet my first fellow hikers of the day, a middle-aged woman guiding six spindly, string-bean boys, maybe nine or ten years old. She totes a pack bursting with lunches; the bean-boys bustle and bumble about her like squirrels. Squirrelly bean boys.

One actually says, “Are we there yet?” Two babble nonsense about “marry-ja-wanna” and heroin. Another: “It feels like I’m in an airplane” Still another climbs up the side of a big cairn, constructed over years from hundreds of stones, and he’s got a rock in one hand and clearly intends to cherry-plant it. “No, no,” chides the woman, “that’s not safe.” He backs off and I jump in: “It’s bad karma to touch a cairn,” I instruct, “very bad luck.” Bean-boy behind me: “Really?” “Absolutely,” I continue, “very bad juju,” and now I’m the eight-foot-tall juju dude they’ll laugh about in the cafeteria tomorrow. “I don’t care because I don’t believe in that stuff,” states the thwarted climber. “I do,” asserts his companion because he really does or really wants to or can’t stop himself from saying night if the kid with the rock says day. Meanwhile, the poor woman-in-charge stares at me, hands on hips. I head up the trail.

About 36 people lounge about the peak; everyone’s having a good time, laughing and sharing cookies and looking out across the magnificent sky, across woods and rivers and hills and five New England states. It’s a rare day of ultimate visibility. There’s Mount Washington! (I think.) That quivery, sparkly line to the south – the Hancock Tower! To the east, the whitecaps of the Atlantic Ocean! To the west, the peaks of the Adirondacks and cornfields and prairies and the Rocky Mountains arising! To the north, ice shelves calving off Arctic glaciers… okay, I exaggerate a bit, but you can see a long, long way.

I settle in for lunch and there’s mom with her toddler, changing his diaper. How’d they beat me up here? Must have taken a straight line, but still, impressive. Now the kiddo stumbles to a puddle and pats his palm on the surface; mom keeps a hand on him, gently, not constraining. There’s no wedding ring on her finger. Nearby, a couple of teenagers are eating Subway sandwiches and speaking in Japanese. I ask them if they’ve ever climbed Mt. Fuji in Japan. Yes, says the older one, brightening up, but he didn’t make it up top. We chat about Mt. Fuji’s trails and the tea houses and resting spots along the way, and I mention that it’s the second-most-climbed mountain in the world with Monadnock right behind. This they hadn't known. “Fuji is really crowded,” says the younger boy; on TV, he’s seen lines of people going up and down.

“I’ve heard that,” I say, “but I still want to go there.”

A man with a twangy voice (Texas?) calls the boys over. They gather on a boulder with several other teens, some Asian, some not. “Get closer together,” says the man, and he snaps photos with his phone. “Good work, lads,” he enthuses, and I notice a few smiles because it’s fun, I guess, to be called a lad. When they leave the peak, my new friends wave goodbye and the younger one, I’m not sure why, thanks me. I depart soon after, traveling downhill on the Pumpelly Trail, then Red Spot, then Cascade Link, then White Dot. On steep areas I hold my hiking poles in one hand, using the other to grab tree trunks and cracks in rock faces.

I settle in for lunch and there’s mom with her toddler, changing his diaper. How’d they beat me up here? Must have taken a straight line, but still, impressive. Now the kiddo stumbles to a puddle and pats his palm on the surface; mom keeps a hand on him, gently, not constraining. There’s no wedding ring on her finger. Nearby, a couple of teenagers are eating Subway sandwiches and speaking in Japanese. I ask them if they’ve ever climbed Mt. Fuji in Japan. Yes, says the older one, brightening up, but he didn’t make it up top. We chat about Mt. Fuji’s trails and the tea houses and resting spots along the way, and I mention that it’s the second-most-climbed mountain in the world with Monadnock right behind. This they hadn't known. “Fuji is really crowded,” says the younger boy; on TV, he’s seen lines of people going up and down.

“I’ve heard that,” I say, “but I still want to go there.”

A man with a twangy voice (Texas?) calls the boys over. They gather on a boulder with several other teens, some Asian, some not. “Get closer together,” says the man, and he snaps photos with his phone. “Good work, lads,” he enthuses, and I notice a few smiles because it’s fun, I guess, to be called a lad. When they leave the peak, my new friends wave goodbye and the younger one, I’m not sure why, thanks me. I depart soon after, traveling downhill on the Pumpelly Trail, then Red Spot, then Cascade Link, then White Dot. On steep areas I hold my hiking poles in one hand, using the other to grab tree trunks and cracks in rock faces.

Halfway, I stop to tie my bootlaces and finish the water bottle – it's better to stay hydrated than save a bit. A small plane chutters by a couple thousand feet above. This causes me to wonder how much carbon I emitted during my trip to London two weeks ago. What’s my responsibility for climate change? And how did that flight compare to my eleven, and soon twelve, car trips back and forth from Somerville to Mount Monadnock during the past year?

The results are surprising. I would have thought that the CO2 exhalations from 2,000 miles of driving alone in a 1993 Toyota Camry would exceed one person's allotment from a 6,550-mile ride in a crowded plane. Not so, and not even close if you account for water vapor emissions (which trap heat) as well as the amplified effects of CO2 released at altitude, also known as radiative forcing. Therefore, a dozen trips to climb my great granite friend: .84 tons of carbon. One hop across the ocean and back: 3.27 tons. Cost of carbon offsets (carbonfund.org) for all these journeys: $42.17. Just pop in those 16 VISA numbers, plus expiration date. Renewable energy programs financed in India. Conscience cleared.

There’s a problem, though. Carbon offsets, as the Brits say, are a bit dodgy. Yes, if properly executed, they make up for environmental misdeeds, adding good to the future in trade for bad in the past. But offsets cannot undo what’s been done. They should be considered, perhaps, a form of virtual repentance, of digital teshuvah. Sooner, and not later, we must stop offsetting our screw-ups and start doing better the first time around.

I’m still feeling strong and finish the hike at a brisk clip. Wouldn’t you know it, there’s mom and toddler again in the parking lot. Did they fly up and down? Chilling on a bench, the mountain-conquering child slurps at his sippy cup, legs kicking, while his mother fusses over the child carrier. Slurp, slurp, kick, kick, fuss, fuss. Life goes on.

The results are surprising. I would have thought that the CO2 exhalations from 2,000 miles of driving alone in a 1993 Toyota Camry would exceed one person's allotment from a 6,550-mile ride in a crowded plane. Not so, and not even close if you account for water vapor emissions (which trap heat) as well as the amplified effects of CO2 released at altitude, also known as radiative forcing. Therefore, a dozen trips to climb my great granite friend: .84 tons of carbon. One hop across the ocean and back: 3.27 tons. Cost of carbon offsets (carbonfund.org) for all these journeys: $42.17. Just pop in those 16 VISA numbers, plus expiration date. Renewable energy programs financed in India. Conscience cleared.

There’s a problem, though. Carbon offsets, as the Brits say, are a bit dodgy. Yes, if properly executed, they make up for environmental misdeeds, adding good to the future in trade for bad in the past. But offsets cannot undo what’s been done. They should be considered, perhaps, a form of virtual repentance, of digital teshuvah. Sooner, and not later, we must stop offsetting our screw-ups and start doing better the first time around.

I’m still feeling strong and finish the hike at a brisk clip. Wouldn’t you know it, there’s mom and toddler again in the parking lot. Did they fly up and down? Chilling on a bench, the mountain-conquering child slurps at his sippy cup, legs kicking, while his mother fusses over the child carrier. Slurp, slurp, kick, kick, fuss, fuss. Life goes on.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed