This is about my October hike that took place in November.

Life, and death, conspired to keep me away during Mount Monadnock’s most popular month, as tens of thousands of devotees ascended its well-worn shoulders to witness the colorful glory of peak foliage in New England. The idea was to cap this twelve-month cycle of hikes with a fun romp in mid-October with my wife Elahna and our friends Andy, Leah and Julia, but we postponed due to work demands. Then the rescheduled hike for Saturday, October 24th was shelved when Elahna’s mother, Hadassah, collapsed and was rushed to Massachusetts General Hospital. Diagnosed with colon cancer, her condition deteriorated and she died on October 28th at 12:17 a.m. with Elahna and me at her bedside. We picked out a burial plot that same day, stumbled through the funeral and sat shivah for seven, long days.

All this year, I’d been worried about my mother dying. Not once did I consider that Elahna’s mom, age 80 and beset by chronic health issues but mobile and feisty as ever, could vanish in a blink. It just wasn’t on our radar. No one knew she was this sick. And so we torture ourselves with laments. What, I wonder, might Hadassah say to all this? Der mentsh trakht un got lakht, she’d probably say. That’s Yiddish for “Man plans and G-d laughs.” She’d pronounce the words – how she loved words! – in that thick Israeli accent she harbored since her arrival in the USA in 1961, and then she’d ruefully chuckle. The photo above shows toddler Elahna with her proud mommy. In it, everything seems possible.

I embark for Monadnock on the sixth day of shivah, which is the week-long ritual period of mourning in Judaism. Technically, you’re not supposed to pursue activities beyond receiving guests, reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish and remembering the deceased, but I needed a break from the gloom and didn’t want to risk another tragedy or fluke injury or earthquake pushing this hike into December or 2016. As I approach the mountain, the blaze of orange, red and yellow leaves in the surrounding woods has faded to embers. Peak foliage, the ranger at the gate tells me, passed a week or two ago. But “there are patches,” he asserts hopefully, outlier trees still trumpeting peak beauty. This cheers me, but turns out to be untrue.

Life, and death, conspired to keep me away during Mount Monadnock’s most popular month, as tens of thousands of devotees ascended its well-worn shoulders to witness the colorful glory of peak foliage in New England. The idea was to cap this twelve-month cycle of hikes with a fun romp in mid-October with my wife Elahna and our friends Andy, Leah and Julia, but we postponed due to work demands. Then the rescheduled hike for Saturday, October 24th was shelved when Elahna’s mother, Hadassah, collapsed and was rushed to Massachusetts General Hospital. Diagnosed with colon cancer, her condition deteriorated and she died on October 28th at 12:17 a.m. with Elahna and me at her bedside. We picked out a burial plot that same day, stumbled through the funeral and sat shivah for seven, long days.

All this year, I’d been worried about my mother dying. Not once did I consider that Elahna’s mom, age 80 and beset by chronic health issues but mobile and feisty as ever, could vanish in a blink. It just wasn’t on our radar. No one knew she was this sick. And so we torture ourselves with laments. What, I wonder, might Hadassah say to all this? Der mentsh trakht un got lakht, she’d probably say. That’s Yiddish for “Man plans and G-d laughs.” She’d pronounce the words – how she loved words! – in that thick Israeli accent she harbored since her arrival in the USA in 1961, and then she’d ruefully chuckle. The photo above shows toddler Elahna with her proud mommy. In it, everything seems possible.

I embark for Monadnock on the sixth day of shivah, which is the week-long ritual period of mourning in Judaism. Technically, you’re not supposed to pursue activities beyond receiving guests, reciting the Mourner’s Kaddish and remembering the deceased, but I needed a break from the gloom and didn’t want to risk another tragedy or fluke injury or earthquake pushing this hike into December or 2016. As I approach the mountain, the blaze of orange, red and yellow leaves in the surrounding woods has faded to embers. Peak foliage, the ranger at the gate tells me, passed a week or two ago. But “there are patches,” he asserts hopefully, outlier trees still trumpeting peak beauty. This cheers me, but turns out to be untrue.

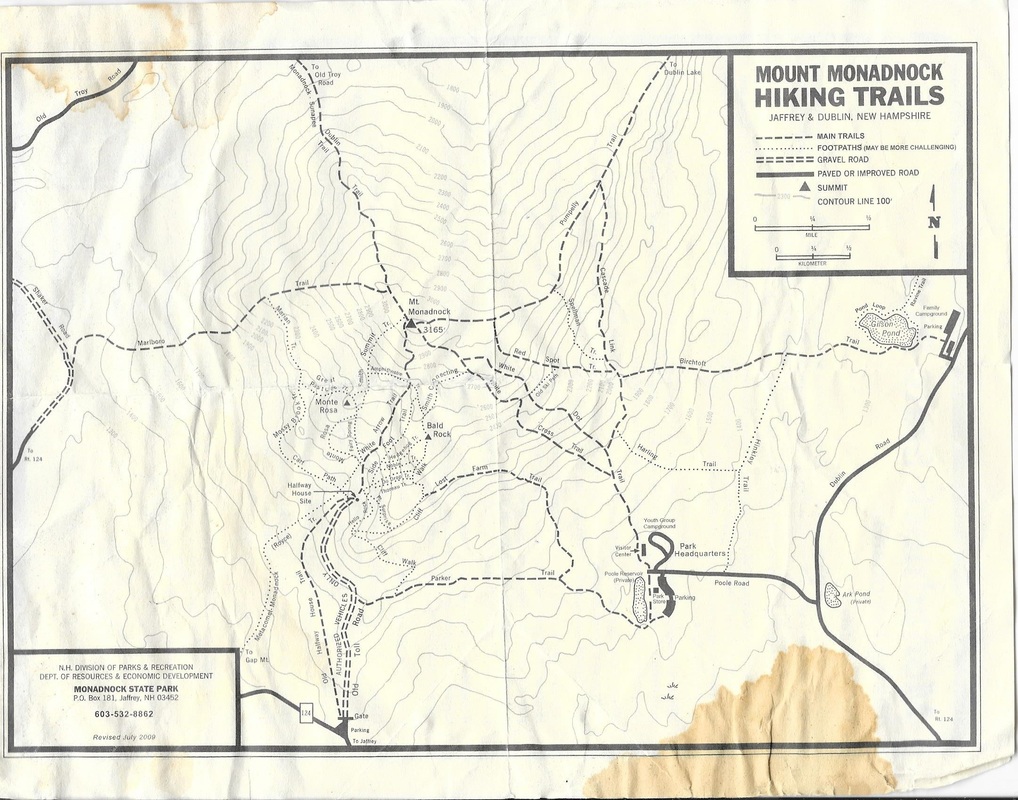

I park my Prius Zipcar – the plan was to take Hadassah’s 1993 Toyota Corolla, but its alternator expired after the funeral – and I head up the most traveled avenue, the White Dot Trail. A sign I’ve never noticed before labels Monadnock as a “carry-in, carry-out” park regarding trash, and it’s a measure of my somber temperament that I comment, maybe to myself and maybe out loud: yes, they carry you in, they carry you out. From the birthing bed, we’re carried. To the grave, we’re carried again. And I flash onto the fresh image of my wife digging shovelfuls of dirt and dropping them onto her mother’s pine-box coffin, its only flourish a carved Magen David, the star-shaped shield of King David.

It’s a warm day, in the 60s. The wind picks up and rusty oak leaves shudder overhead. I take some shots of a beautifully tangled birch grove and imagine sending them to Hadassah’s email. Just in case you’re still checking your messages, I’d write, here are a few nice pics from my latest hike. Of course, it’s a long shot because she always had trouble opening attachments. Yesterday Elahna concocted an even stranger fantasy, that she’d take photos of herself in the snazzy autumn coat that her mother had ordered but never got a chance to wear and then she’d slide the prints into her gravesite using a garden edger. See, mommy, see how it looks. I was wary, as you can imagine, about leaving her today, and at the door she urged me to “be extra careful” and “keep two hands on the wheel.” She said “I love you” over and over because, of course, the world is unpredictable and unfair and you can’t always count on another chance to do the right thing, to say what’s in your heart. As Elahna keeps repeating, “There was supposed to be more time.”

Young folk in shorts and t-shirts pass me, going up and down. We exchange quick hellos, nothing more. I plop on a rock at the turnoff to the Cascade Link, at the very spot where I once witnessed a young lady yell at her snow-sliding male companion, “I’m not going down on my ass, Larry!” With difficulty, I peel off my long-sleeve shirt and switch the torn black ribbon to the t-shirt beneath. The ribbon symbolizes the act of kriah, the rending and tearing of clothes in grief and anger. Jacob rends and tears like a madman in the Book of Genesis when his lying sons tell him that Joseph is dead. Job does the same for his tribulations, as does King David when his best friend, Yonatan, is killed in battle. Now the wind causes the torn ribbon to flap over my heart.

Okay, that's enough. Time to cheer up. This is supposed to be a blog, not a dirge.

It’s a warm day, in the 60s. The wind picks up and rusty oak leaves shudder overhead. I take some shots of a beautifully tangled birch grove and imagine sending them to Hadassah’s email. Just in case you’re still checking your messages, I’d write, here are a few nice pics from my latest hike. Of course, it’s a long shot because she always had trouble opening attachments. Yesterday Elahna concocted an even stranger fantasy, that she’d take photos of herself in the snazzy autumn coat that her mother had ordered but never got a chance to wear and then she’d slide the prints into her gravesite using a garden edger. See, mommy, see how it looks. I was wary, as you can imagine, about leaving her today, and at the door she urged me to “be extra careful” and “keep two hands on the wheel.” She said “I love you” over and over because, of course, the world is unpredictable and unfair and you can’t always count on another chance to do the right thing, to say what’s in your heart. As Elahna keeps repeating, “There was supposed to be more time.”

Young folk in shorts and t-shirts pass me, going up and down. We exchange quick hellos, nothing more. I plop on a rock at the turnoff to the Cascade Link, at the very spot where I once witnessed a young lady yell at her snow-sliding male companion, “I’m not going down on my ass, Larry!” With difficulty, I peel off my long-sleeve shirt and switch the torn black ribbon to the t-shirt beneath. The ribbon symbolizes the act of kriah, the rending and tearing of clothes in grief and anger. Jacob rends and tears like a madman in the Book of Genesis when his lying sons tell him that Joseph is dead. Job does the same for his tribulations, as does King David when his best friend, Yonatan, is killed in battle. Now the wind causes the torn ribbon to flap over my heart.

Okay, that's enough. Time to cheer up. This is supposed to be a blog, not a dirge.

I resume climbing and it’s an effort. I’m tired from lack of sleep and tight from inactivity, but soon the muscles limber and my thoughts lighten. I cross to the Red Dot Trail and take a break on a jumble of granite slabs with a southern view. It’s all muted greens and darkening reds to bluish hills beyond. A cushion of cirrus clouds sits between the hills and the light-blue sky. Way, way up, a plane emits a gushy contrail. Maybe it’s going to Israel – last year Elahna took Hadassah there for what the old lady presciently called “her last time.” In fact, after receiving her cancer diagnosis in the hospital two weeks ago, she commented that she’d be dead in a few days. No way, we declared, stop it, don’t be ridiculous. Lots of people live with cancer. Besides, you can’t know such a thing, that you’ll be dead within days. Ridiculous. Here, have a drink of water.

Hike, hike, hike – just below tree line I rest on a granite mound riven by long cracks that seem carved by chisel. I sit near a cairn – old friend! – recognized from a winter trek. Then it was spattered with ice and snow; so was I. From here Monadnock’s rocky peak is visible, framed by the tips of pine trees. A couple of stick figures, surely human, move about up there. I munch Trader Joe’s Rainbow’s End trail mix and drink from my leaky City Sports water bottle. On the ride up, the super-peppy woman inside the car radio explained that City Sports had declared bankruptcy. Their strategy to expand from urban locations to suburban malls was a colossal, cash-hemorrhaging flop and now the whole thing had gone under, demonstrating, I guess, that you never know when you’re at your peak, when you should pull back and stop trying to do more, better. When you should simply accept.

For me Hadassah’s death was a tremendous shock, as if I blinked and Monadnock’s great, granite summit was suddenly gone. I take comfort in knowing that such an event is highly unlikely in my lifetime – barring asteroid strike, errant nuclear attack or celestial intervention via a Monty Python-esque flicking finger. But still, you never know for sure.

Hike, hike, hike – just below tree line I rest on a granite mound riven by long cracks that seem carved by chisel. I sit near a cairn – old friend! – recognized from a winter trek. Then it was spattered with ice and snow; so was I. From here Monadnock’s rocky peak is visible, framed by the tips of pine trees. A couple of stick figures, surely human, move about up there. I munch Trader Joe’s Rainbow’s End trail mix and drink from my leaky City Sports water bottle. On the ride up, the super-peppy woman inside the car radio explained that City Sports had declared bankruptcy. Their strategy to expand from urban locations to suburban malls was a colossal, cash-hemorrhaging flop and now the whole thing had gone under, demonstrating, I guess, that you never know when you’re at your peak, when you should pull back and stop trying to do more, better. When you should simply accept.

For me Hadassah’s death was a tremendous shock, as if I blinked and Monadnock’s great, granite summit was suddenly gone. I take comfort in knowing that such an event is highly unlikely in my lifetime – barring asteroid strike, errant nuclear attack or celestial intervention via a Monty Python-esque flicking finger. But still, you never know for sure.

Around two o’clock I arrive up top, joining 18 other people, give or take, come and go. It’s mostly young couples, with a few older, solo acts. One of the young’uns stands over my favorite geodesic marker – yes, I have a favorite one – and I ask him to move his foot so I can tap the round, bronze object imbedded in stone with the tip of my hiking pole. Tradition! He laughs and garbles something unintelligible, or am I just not hearing today? I laugh back and almost start a conversation, but don’t. Then I hunker against a boulder and eat ginger cookies and watch ink-black hawks play and scrap on the north side of the mountain where a rock spur points to Dublin Lake. The view of forest and mountains farther to the north is painterly, bathed in a purplish hue that seems not quite real

Before going down, I walk to the eastern edge of the peak and face Jerusalem where Hadassah was born during the British Mandate, before the state of Israel was born. Where she grew up in the neighborhood of Beit Ungarin abutting an enclave of ultra-Orthodox Jews. Where she cherished and fought with her four sisters and was known as daddy’s favorite and survived the Siege of Jerusalem during Israel’s War of Independence. Where she served in the army, graduated Hebrew University, had a Russian boyfriend with a Vespa and practiced English by reading Perry Mason pulp paperbacks. Where she earned a Fulbright Scholarship that enabled her, she emphatically declared, to “escape” – and so she came to the Land of Opportunity where justice prevails. Soon she found herself with an American husband, an exuberant child and a real job teaching college students.

On a high, granite knoll I face Jerusalem, pull out my iPod and tap the iKaddish app. Lines of Hebrew appear and I say the Mourner’s Kaddish in violation of the rule requiring a minyan of ten fellow Jews for recitation. I figure sitting mountaintop shivah is an extenuating circumstance.

Yit-gadal vi-yit-kadash sm’meih raba

(May his great name grow exalted and sanctified)

B’al’ma di v’ra chir-u-teih

(in the world that he created as he willed)

And so on for twenty more lines, not mentioning mourning or death once; rather, it exalts G-d’s glory again and again. There’s a mountain of books written about the Kaddish, which I haven’t read, but the other day I picked out The Mysteries of the Kaddish from Hadassah’s library (now ours) and gleaned this pearl: the mourner’s prayer praises G-d in order to keep the griever from surrendering to anger at a divine power with the chutzpah to claim a precious, loved one. It keeps us humble, grateful for the gift of life.

Before going down, I walk to the eastern edge of the peak and face Jerusalem where Hadassah was born during the British Mandate, before the state of Israel was born. Where she grew up in the neighborhood of Beit Ungarin abutting an enclave of ultra-Orthodox Jews. Where she cherished and fought with her four sisters and was known as daddy’s favorite and survived the Siege of Jerusalem during Israel’s War of Independence. Where she served in the army, graduated Hebrew University, had a Russian boyfriend with a Vespa and practiced English by reading Perry Mason pulp paperbacks. Where she earned a Fulbright Scholarship that enabled her, she emphatically declared, to “escape” – and so she came to the Land of Opportunity where justice prevails. Soon she found herself with an American husband, an exuberant child and a real job teaching college students.

On a high, granite knoll I face Jerusalem, pull out my iPod and tap the iKaddish app. Lines of Hebrew appear and I say the Mourner’s Kaddish in violation of the rule requiring a minyan of ten fellow Jews for recitation. I figure sitting mountaintop shivah is an extenuating circumstance.

Yit-gadal vi-yit-kadash sm’meih raba

(May his great name grow exalted and sanctified)

B’al’ma di v’ra chir-u-teih

(in the world that he created as he willed)

And so on for twenty more lines, not mentioning mourning or death once; rather, it exalts G-d’s glory again and again. There’s a mountain of books written about the Kaddish, which I haven’t read, but the other day I picked out The Mysteries of the Kaddish from Hadassah’s library (now ours) and gleaned this pearl: the mourner’s prayer praises G-d in order to keep the griever from surrendering to anger at a divine power with the chutzpah to claim a precious, loved one. It keeps us humble, grateful for the gift of life.

I head down the White Cross Trail and the sun is lowering in the west, casting slanted shadows on the granite slabs. Hopping over puddles, I’m careful not to slip on slick leaves shrouding rocks. Soon I meet a golden chipmunk gnawing an acorn and closely encounter a downy woodpecker, all black and white with a ruby red kippah on top. Hanging on a tree trunk, he gives me the gimlet eye. Then, bam, I’m in a birch grove – hundreds of shy, spindly tree folk, entirely bare of their yellow, isosceles triangle-shaped leaves. I lean over, pick one up. Its brown veins outline a tree inside the leaf – but not a gangly birch, no, the tree inside is a mighty, spreading oak or elm or baobab. The little birch leaf dreams of something greater. Have I noticed this before? Maybe, but it feels like the first time. The leaf’s edges zigzag like a haphazard staircase or a graph line going up, up, up to a peak, to its point-absolute, and then meandering down, down, down the other side.

The day before this climb, a young couple on our street came to the house during shivah hours. They brought their newborn baby, Sadie May, swaddled in a white blanket streaked with rainbows. She was asleep, her little pink face faintly scrunched, and I held her in my arms for a while. The couple hadn’t met Hadassah, so we mostly shared neighborhood gossip. I found myself whispering a lullaby to Sadie May, one my mother sang. The bear went over the mountain, the bear went over the mountain, the bear went over the mountain to see what he could see…and what, you might ask, did the brave bear see? The other side of the mountain, the other side of the mountain, the other side of the mountain was all that he could see…an outcome, frankly, that disappointed little boy Hal.

What, no fantastical land? No sparkling city on a hill? No answers to my questions, no solutions to my problems, no clues to the dark, unpredictable future?

That’s right, none of that. Just the other side of the mountain. But now, in the middle of my life, I’m okay with that reality because I know that the mountain, not the next captivating vista, is the thing. Every side of the mountain is fascinating and endlessly revealing in its own right. Every side of the mountain is an adventure, a new test for the curious climber. Every side of the mountain leads to the peak and, when you’re ready, takes you back down.

The day before this climb, a young couple on our street came to the house during shivah hours. They brought their newborn baby, Sadie May, swaddled in a white blanket streaked with rainbows. She was asleep, her little pink face faintly scrunched, and I held her in my arms for a while. The couple hadn’t met Hadassah, so we mostly shared neighborhood gossip. I found myself whispering a lullaby to Sadie May, one my mother sang. The bear went over the mountain, the bear went over the mountain, the bear went over the mountain to see what he could see…and what, you might ask, did the brave bear see? The other side of the mountain, the other side of the mountain, the other side of the mountain was all that he could see…an outcome, frankly, that disappointed little boy Hal.

What, no fantastical land? No sparkling city on a hill? No answers to my questions, no solutions to my problems, no clues to the dark, unpredictable future?

That’s right, none of that. Just the other side of the mountain. But now, in the middle of my life, I’m okay with that reality because I know that the mountain, not the next captivating vista, is the thing. Every side of the mountain is fascinating and endlessly revealing in its own right. Every side of the mountain is an adventure, a new test for the curious climber. Every side of the mountain leads to the peak and, when you’re ready, takes you back down.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed