Today we ascend Monadnock from the north on the long, gradual Pumpelly Trail, three dauntless hikers hoofing nine miles up and back in a seamless shroud of cloud, and hold on there, you ask, what the heck is a Pumpelly?

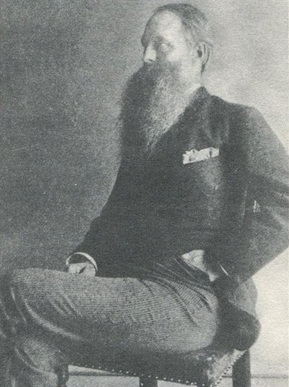

In this case, it’s a Raphael Pumpelly (1837-1923), geology professor, archeologist, explorer (China, Turkmenistan) and beard grower extraordinaire. He “summered,” as the heedless rich say, in Dublin on the northern shore of the mountain, bestirring himself in 1884 to cut his namesake trail. In his autobiography, Pumpelly comments on Dublin’s pampered children – “When not on their ponies they spend their days exploring the mysteries of Monadnock” – and advises his Harvard-bound son to write a freshman theme about the “wild and rugged mass of Monadnock” by camping sunset to sunrise at its peak. There, counsels the old goat, “Watch the unfolding of the eternal drama that inspired religions of the ancient world,” faithfully record what you see and feel, and “don’t use similes.”

In honor of Raphael Pumpelly and his righteous beard, I pledge in this blog entry to work like a trio of Turkmen tinkerers to avoid similes. Alliteration – I make no promises.

My hiking companions are Russell, an old friend, and his girlfriend Bar. We meet at Timoleon’s “Family” Restaurant in Keene, west of Monadnock. I’d last eaten here maybe 20 years ago and the place seems frozen in time. I order two eggs over easy, home fries, toast and coffee, plus a slice of strawberry-rhubarb pie for Russell. The damage – $6.10. My old favorite chicken croquettes with apple and “special” sauces is still on the menu – $5.50. On the back wall hangs an oil painting, Monadnock in Autumn by Helena N. Putnam, featuring a maple tree ablaze and Monadnock’s rocky nib in the distance.

Russell points to an autographed photo of Telly Savalas next to the pie cabinet. It’s young Telly, pre-Kojak, with no lollipop planted in his kisser, no scrawled “Who loves ya, baby?” Nearby sits a framed headshot of a guy with a fat, 1980s tie. “Who’s that?” I ask the man behind the counter who happens to be the 88-year-old owner of the restaurant, Timoleon Chakolos. “That’s Bob Clark,” he says. As in, who else would it be and were you born under a log? It seems Bob was a friend from the insurance agency down the street who came in all the time. A big eater? I ask. Long pause. “He did all right,” drawls Mr. Chakolos.

In this case, it’s a Raphael Pumpelly (1837-1923), geology professor, archeologist, explorer (China, Turkmenistan) and beard grower extraordinaire. He “summered,” as the heedless rich say, in Dublin on the northern shore of the mountain, bestirring himself in 1884 to cut his namesake trail. In his autobiography, Pumpelly comments on Dublin’s pampered children – “When not on their ponies they spend their days exploring the mysteries of Monadnock” – and advises his Harvard-bound son to write a freshman theme about the “wild and rugged mass of Monadnock” by camping sunset to sunrise at its peak. There, counsels the old goat, “Watch the unfolding of the eternal drama that inspired religions of the ancient world,” faithfully record what you see and feel, and “don’t use similes.”

In honor of Raphael Pumpelly and his righteous beard, I pledge in this blog entry to work like a trio of Turkmen tinkerers to avoid similes. Alliteration – I make no promises.

My hiking companions are Russell, an old friend, and his girlfriend Bar. We meet at Timoleon’s “Family” Restaurant in Keene, west of Monadnock. I’d last eaten here maybe 20 years ago and the place seems frozen in time. I order two eggs over easy, home fries, toast and coffee, plus a slice of strawberry-rhubarb pie for Russell. The damage – $6.10. My old favorite chicken croquettes with apple and “special” sauces is still on the menu – $5.50. On the back wall hangs an oil painting, Monadnock in Autumn by Helena N. Putnam, featuring a maple tree ablaze and Monadnock’s rocky nib in the distance.

Russell points to an autographed photo of Telly Savalas next to the pie cabinet. It’s young Telly, pre-Kojak, with no lollipop planted in his kisser, no scrawled “Who loves ya, baby?” Nearby sits a framed headshot of a guy with a fat, 1980s tie. “Who’s that?” I ask the man behind the counter who happens to be the 88-year-old owner of the restaurant, Timoleon Chakolos. “That’s Bob Clark,” he says. As in, who else would it be and were you born under a log? It seems Bob was a friend from the insurance agency down the street who came in all the time. A big eater? I ask. Long pause. “He did all right,” drawls Mr. Chakolos.

It takes a while for me to find the trailhead. Bar seems distracted, perhaps skeptical of my competence, but we get started by mid-morning and it’s just us clomping along between tall trees, mossed-over rocks and promiscuous outbreaks of fern. The sky is white-on-white, the cloud bank low. Russell, a fit 60, is a former marathoner; Bar, an even fitter 62, once hiked the Appalachian Trail stem to stern, Georgia to Maine, and she’s contemplating another go, says Russell, “before the window closes.” Within minutes, she perks up. “It’s like a walk in the woods,” she says, and I wonder if she expected a paved trail clogged with tourists.

I’m impressed by their knowledge of flowers and birds – Bar, especially, who hears a ruffed grouse in the underbrush, ruffing and grousing about, and identifies a woodpecker as the fabled yellow-bellied sapsucker. I must admit to hearing no sucking of sap, nor do I spy a yellow belly on this industrious, red-masked fellow as he attacks bugs on a tree trunk, bunka, bunka, bunka, bunka. The Chirp! USA app on my iPod, however, soon confirms Bar as bird queen. About an hour in, Russell points out sheep laurel with its pendent clusters of red flowers and encapsulated fruit. Sheep laurel is especially toxic to, well, sheep, but it can also take down a human. Symptoms include headaches, diarrhea, sweating, excessive salivation, tingling skin, impaired coordination, green froth around the mouth, depression and recumbency (an inability to stand). Actually, I experience many of those conditions on a regular basis. Maybe someone is slipping sheep laurel into my salad.

On the first steep area, we encounter a trail crew of a dozen dirty, sweaty guys in their 20s and 30s, volunteering for the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests. With shovels and crowbars, they’re moving huge rocks to create a staircase and a water bar to ease erosion. Fixing the Pumpelly Trail, says one, should take about 15 years. Other than two hikers coming down and a gaggle of young folk scarfing Oreos just below the peak, these are the only people we meet on the way up.

I’m impressed by their knowledge of flowers and birds – Bar, especially, who hears a ruffed grouse in the underbrush, ruffing and grousing about, and identifies a woodpecker as the fabled yellow-bellied sapsucker. I must admit to hearing no sucking of sap, nor do I spy a yellow belly on this industrious, red-masked fellow as he attacks bugs on a tree trunk, bunka, bunka, bunka, bunka. The Chirp! USA app on my iPod, however, soon confirms Bar as bird queen. About an hour in, Russell points out sheep laurel with its pendent clusters of red flowers and encapsulated fruit. Sheep laurel is especially toxic to, well, sheep, but it can also take down a human. Symptoms include headaches, diarrhea, sweating, excessive salivation, tingling skin, impaired coordination, green froth around the mouth, depression and recumbency (an inability to stand). Actually, I experience many of those conditions on a regular basis. Maybe someone is slipping sheep laurel into my salad.

On the first steep area, we encounter a trail crew of a dozen dirty, sweaty guys in their 20s and 30s, volunteering for the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests. With shovels and crowbars, they’re moving huge rocks to create a staircase and a water bar to ease erosion. Fixing the Pumpelly Trail, says one, should take about 15 years. Other than two hikers coming down and a gaggle of young folk scarfing Oreos just below the peak, these are the only people we meet on the way up.

Blueberries! Blueberries! The tiny fruit – some dusky blue, others green and pinkish – congregate on low bushes. The taste of blueberry is faint with even the ripest ones, so I shovel several into my mouth to get a good blueberry boil going. And onward we tromp into the loitering mist – not a scrap of sun or blue sky – as Russell and I reminisce about our year (1989?) working together at Campus Crossroads, a company hired by small colleges to get them big publicity. It’s fun to respin the tale of my epic efforts to gain media coverage for the Rat Olympics at Kalamazoo College, and I mean actual rats trained by actual psychology students to run steeplechase and dive from platforms. Then Russell, a skillful writer, tells me about his new book project on gardening in the time of climate change, and I can’t help but worry when I hear that he’s bravely turned down a book contract because the publisher wanted him to exclude personal experiences tending his garden.

Are you sure? Yes, he says. The personal, that’s the whole point of it. And he’s right – how we make our way through this changing world as we ourselves are changing, absolutely, that is the point. But many people don’t agree. And onward we tromp.

Above tree line, visibility recedes to 15 yards in every direction (except down, where it’s less). It’s okay, though, because Raphael Pumpelly’s trail is now marked by huge, unmistakable cairns, rock pyramids as big as…sorry, no similes today…they were really big, these piles of rocks, and then, whoosh, whomp, my first fall of the day. Down on my butt, nothing fancy. The granite slabs underfoot are slick and glistening with cloud vapor, so on this final stretch across Monadnock’s bald top I strive to securely plant my boots’ thick soles. (I’ve been breaking in a new pair, the Vasque Breeze 2.0 GTX – comfortable, no blisters yet.) After passing the aforementioned kids mainlining Oreos, we make our slipping scramble to the peak where, remarkably, a crowd has gathered.

“It’s like spending a week in the Provincetown dunes,” says Russell, “and then going into town.” Fortunately, no one’s clutching plastic shopping bags or licking ice cream cones, praise be to the mountain gods, but it is a bit of a jostle moving through 30 or so happy souls swept up here from tributary trails. I show my hiking buddies where to tap their poles on the geodesic plaques as per LaCroix tradition. They oblige. We stare out. The view from the summit is absolutely…nothing but white. White, everywhere. No fields, mountains, glints of city and sea. We’re socked-in and cloud surrounded, north, west, south, east and up.

White as…

Are you sure? Yes, he says. The personal, that’s the whole point of it. And he’s right – how we make our way through this changing world as we ourselves are changing, absolutely, that is the point. But many people don’t agree. And onward we tromp.

Above tree line, visibility recedes to 15 yards in every direction (except down, where it’s less). It’s okay, though, because Raphael Pumpelly’s trail is now marked by huge, unmistakable cairns, rock pyramids as big as…sorry, no similes today…they were really big, these piles of rocks, and then, whoosh, whomp, my first fall of the day. Down on my butt, nothing fancy. The granite slabs underfoot are slick and glistening with cloud vapor, so on this final stretch across Monadnock’s bald top I strive to securely plant my boots’ thick soles. (I’ve been breaking in a new pair, the Vasque Breeze 2.0 GTX – comfortable, no blisters yet.) After passing the aforementioned kids mainlining Oreos, we make our slipping scramble to the peak where, remarkably, a crowd has gathered.

“It’s like spending a week in the Provincetown dunes,” says Russell, “and then going into town.” Fortunately, no one’s clutching plastic shopping bags or licking ice cream cones, praise be to the mountain gods, but it is a bit of a jostle moving through 30 or so happy souls swept up here from tributary trails. I show my hiking buddies where to tap their poles on the geodesic plaques as per LaCroix tradition. They oblige. We stare out. The view from the summit is absolutely…nothing but white. White, everywhere. No fields, mountains, glints of city and sea. We’re socked-in and cloud surrounded, north, west, south, east and up.

White as…

What would young Pumpelly have written for his freshman theme if he’d spent the night in this cottony soup? What melancholy screed might have poured from his fountain pen? For myself, I like the change-of-pace sensation, the way the mist leaves expectations utterly unfulfilled. Perspective is obscured in this place and, if not for the memory of three-plus hours of climbing, I might believe that we’ve wandered onto a sea-level jetty or inside a Hollywood sound stage with fog and wind machines churning and extras fake-celebrating. It could be one of those am-I-dreaming-or-in-heaven scenes and here comes the executive angel or G-d himself, looking very much like Morgan Freeman.

Without visual cues, there’s no way to know that we’re 3,165 feet above sea level on a lone mountain in New England. I suppose a smart phone with GPS could provide confirmation, if I had one, or maybe Bar could identify the call of a bird that only lives at altitude. If I were Mark Twain, as related in his travel tale Ascending the Riffelberg, I’d direct my porters to start a fire, lay on a cauldron of water and boil thermometers. As we’ve all learned and forgotten, water boils at 212 degrees Fahrenheit, but the boiling point is reduced by about one degree for each 500-feet increase in elevation. So here atop my great granite friend, a boiled thermometer should read about 196 degrees.

Or I can just take it on faith.

Lunchtime. Russell gobbles a peanut butter-and-raisin sandwich so overstuffed it resembles a burrito, Bar picks at leftover chicken and roasted veggies, and I scarf an apple, trail mix, crackers and two PB&Js. Then we head down. And I start falling. First my feet slip on a slick, steep slab and I roll ridiculously into a narrow gorge. No problem, I meant to do that. Then, minutes later, I slide off another wet rock and land ludicrously in a patch of heather, flat on my back, arms spread, poles akimbo. Russell can’t help chuckling and praises my choice of destination. Bar looks perturbed – what’s wrong with this guy? – or perhaps it’s because we’re on the wrong trail by mistake and need to go back up. On the brief re-ascent, I can’t remember feeling so shaky, so klutzy on Monadnock. I did brush my hand across that sheep laurel – enough to catch a bout of recumbency? Is green froth around the mouth next?

Without visual cues, there’s no way to know that we’re 3,165 feet above sea level on a lone mountain in New England. I suppose a smart phone with GPS could provide confirmation, if I had one, or maybe Bar could identify the call of a bird that only lives at altitude. If I were Mark Twain, as related in his travel tale Ascending the Riffelberg, I’d direct my porters to start a fire, lay on a cauldron of water and boil thermometers. As we’ve all learned and forgotten, water boils at 212 degrees Fahrenheit, but the boiling point is reduced by about one degree for each 500-feet increase in elevation. So here atop my great granite friend, a boiled thermometer should read about 196 degrees.

Or I can just take it on faith.

Lunchtime. Russell gobbles a peanut butter-and-raisin sandwich so overstuffed it resembles a burrito, Bar picks at leftover chicken and roasted veggies, and I scarf an apple, trail mix, crackers and two PB&Js. Then we head down. And I start falling. First my feet slip on a slick, steep slab and I roll ridiculously into a narrow gorge. No problem, I meant to do that. Then, minutes later, I slide off another wet rock and land ludicrously in a patch of heather, flat on my back, arms spread, poles akimbo. Russell can’t help chuckling and praises my choice of destination. Bar looks perturbed – what’s wrong with this guy? – or perhaps it’s because we’re on the wrong trail by mistake and need to go back up. On the brief re-ascent, I can’t remember feeling so shaky, so klutzy on Monadnock. I did brush my hand across that sheep laurel – enough to catch a bout of recumbency? Is green froth around the mouth next?

Before long we find the Pumpelly Trail and make good time on the descent, when not falling. Now Russell has taken up this time-honored tribute to gravity. Booink, whoosh, splat! Don’t worry, I say, you’re still three falls behind me. He resumes more cautiously, and all’s well until he slips down an embankment. Blood streams from Russell’s elbows, which he employed as dirt-breaks. Bar, blessed with balance and shortness, apparently never falls. Or hops up so quickly we don’t notice. “Oh, you boys,” she says, and whips a first aid kit from her pack. Out come ointment, rolls of white medical tape and great gobs of gauze, and in a jiffy Russell’s wounds are wound up. It’s kind of sweet, watching her attend to her man. Then she scurries far ahead on the trail because, after all, how much of this nonsense can a veteran AT thru-hiker take?

Now and then, however, we come upon her relaxing on a rock. She gives us the gimlet eye, searching for fresh, running blood or protuberant bones. At one juncture, she points out the trilling call of the Rufous-sided towhee. “Drink your tea,” it insists, “drink your tea.” About halfway down the mountain, we three witness the day’s only break in the cloud pack. A wind shearing across Monadnock’s northern shoulder rips a ragged hole in the haze and – look, there it is! – we glimpse the world below: green fields, slate-blue lakes and forests running to forever. Here and there, a black river of road or hillside mansion. This unveiling lasts at best a few minutes – celestial reward for our perseverance, I fantasize – and then the wind fades and the show closes. Cloud re-engulfs our side of the mountain.

Soon Pumpelly levels off and the conversation turns to the challenges of being fathers to adult children – especially, as in our cases, when divorce and its never-ending ramifications complicate matters. To say the least. “It’s a process,” Russell says, and I agree, and isn’t that the way whether you’ve got a bird’s eye view for a hundred miles with all the comforting clarity that comes with that, a view as reassuring as a well-hewn simile, or if you’re hiking into cloudy whiteness and witnessing trees, cairns, hikers and birds appear and disappear from thin air, as if conjured. It’s an unpredictable process, a fumbling forward, whether you’re climbing on dry trail or slip-sliding away.

For the last quarter-hour, Russell and I carry two big rocks that he wants to bring home for his climate-changed garden. “I can look at them,” he says, “and know where they came from.” Bar’s waiting at the bottom, smiling; when we part for the day, she surprises me with a big hug. Their car turns around on the gravel road, disappears, and I change into sandals and commence itching an awful scrape on my left calf, a divot of dirt and blood.

Tomorrow I will ache. But today, it’s another great day on the mountain.

Now and then, however, we come upon her relaxing on a rock. She gives us the gimlet eye, searching for fresh, running blood or protuberant bones. At one juncture, she points out the trilling call of the Rufous-sided towhee. “Drink your tea,” it insists, “drink your tea.” About halfway down the mountain, we three witness the day’s only break in the cloud pack. A wind shearing across Monadnock’s northern shoulder rips a ragged hole in the haze and – look, there it is! – we glimpse the world below: green fields, slate-blue lakes and forests running to forever. Here and there, a black river of road or hillside mansion. This unveiling lasts at best a few minutes – celestial reward for our perseverance, I fantasize – and then the wind fades and the show closes. Cloud re-engulfs our side of the mountain.

Soon Pumpelly levels off and the conversation turns to the challenges of being fathers to adult children – especially, as in our cases, when divorce and its never-ending ramifications complicate matters. To say the least. “It’s a process,” Russell says, and I agree, and isn’t that the way whether you’ve got a bird’s eye view for a hundred miles with all the comforting clarity that comes with that, a view as reassuring as a well-hewn simile, or if you’re hiking into cloudy whiteness and witnessing trees, cairns, hikers and birds appear and disappear from thin air, as if conjured. It’s an unpredictable process, a fumbling forward, whether you’re climbing on dry trail or slip-sliding away.

For the last quarter-hour, Russell and I carry two big rocks that he wants to bring home for his climate-changed garden. “I can look at them,” he says, “and know where they came from.” Bar’s waiting at the bottom, smiling; when we part for the day, she surprises me with a big hug. Their car turns around on the gravel road, disappears, and I change into sandals and commence itching an awful scrape on my left calf, a divot of dirt and blood.

Tomorrow I will ache. But today, it’s another great day on the mountain.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed