Footnotes to a Book About the Future that I Abandoned Several Years Ago*

*In 2011, to be exact. These footnotes, found below leaping from the runaway sentences they were born from, were probably the best parts of a series of hybrid essays, part journalism, part memoir, about the year 2050. I could never shape the darn thing into a coherent whole, maybe because the book was less about that particular year – I mean, really, who knows? – than about the idea of the future and what it means from personal and philosophical perspectives. Given that I had no “platform,” in publisher-speak, as either a philosopher or futurist, the project was a long shot. And it didn’t come in.

Please note the bonus, new material from July, 2016: blissfully short footnotes to the footnotes to the abandoned book! It’s fun to see how things have changed, or not.

Oh, one more thing. Here are some background details about the author that may clarify matters: my age – 55; brothers and sisters – four; mother – elderly, in nursing home; father – alcoholic, died when I was 15; wife – Elahna; daughter – Kelsey, age 26. I got divorced from her mother when she was five. Also I teach at a college in Boston, write stuff, garden, like Star Trek, enjoy hiking, etc. I worry, yet life’s good. Okay, here goes –

@ @ @

(from page 6) The year 2050 has acquired a totemic quality as a marker, a dateline, a kind of historical crossroads.*

*Like 2050 is now, 1984 was much anticipated then. Its arrival has since become celebrated for not ushering in the Orwellian world of Nineteen Eighty-four – or so says the monolithic mass media directing us how to think and feel and behave. The year 2000 fascinated fans of Nostradamus who believed that the cosmos would collapse at midnight of the new millennium, as well as technologists who predicted a Y2K global computer glitch meltdown. An internet-powered cult has lately formed around 2012 as the Doomsday Year, based on dubious interpretations of the Mayan Long Count calendar which ends – just ends! – on December 21, 2012. Plus there’s a very loud movie, 2012, by the same dudes who blew up the White House in Independence Day, and haven’t you read the psychedelic future history, 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl, in which we stand at “the juncture between one world and the next,” according to the book’s author Daniel Pinchbeck. He admits to not knowing if the next world will be a famine-torn hell or “a new planetary culture based on empathy.” The latter would be nice.*

*Why did I tease poor Pinchbeck? Maybe he’s right; maybe we are hitting an historical inflection point in which muddling along won’t cut it anymore. 2050, btw, is still trotted out in 2016 as the measuring milestone for the future, for no reason other than its nice roundedness. Also, its digits add up to seven and G-d took seven days; hmmm…

@ @ @

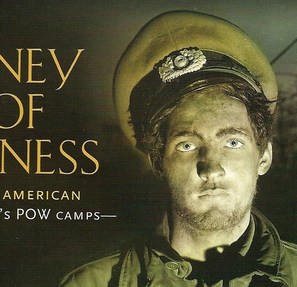

(page 8) David asked me why the POW on the cover of my book Journey out of Darkness looked like me. His face, like mine. The comparison shocked me, in fact, but for some reason I just laughed and nodded. Yeah, that’s crazy, isn’t it?*

*When I returned from San Francisco, I looked closely at the man on the cover of Journey Out of Darkness. Yes, he does resemble me – the me of 25-30 years ago, the screwed-up college me. The man’s eyes are so sad and vacant that it’s unnerving. Do I still look that way sometimes? The answer, alas, is yes. Another weird thing about the photo: this American POW is wearing a German naval cap; where’d that come from?*

*Was the cap screw-up an omen? And a strange omen, indeed, if this American POW is a member of the German navy. After Journey came out in 2007, I expected to publish more books but the future thing capsized and the project about hiking the length of Israel is stuck because I haven’t finished the Negev Desert segment due to heart problems and my Cold War book is still notes and no wonder those eyes are so sad and vacant…maybe I should go to Germany, see the Wall, Berlin, the land where the POWs were starved…take a train to Auschwitz and the bloodlands…do some kind of penance…is that what the cap means?

@ @@

(page 10) Sure, thinking ahead is prudent – toting an umbrella,* building a college or retirement fund, keeping your job skills current, sliding a dime in the leather slot of your penny loafer just in case you get stranded and need to make a phone call, as my mother did in her Depression-era girlhood – but excessive concentration on the future can be a wearying pursuit, devoid of spontaneity, and a convenient excuse for avoiding present responsibilities, opportunities, and horrors.

*Isn’t it sublime, every now and then, to be caught in the rain? When she was ten years-old, my daughter Kelsey and I took a trip to Washington, D.C. Without checking the weather forecast one morning – this being that long-ago, misty era before GPS-enabled smartphone news alerts – we walked down the Mall to the Lincoln Memorial. Once inside, as we read the marble-chiseled words of the Gettysburg Address in the great man’s shadow, the heavens split open and, boy, did it ever rain. We stood with four score or so people on the lip of the monument, looking with Lincoln at the water bounding off the surface of the Reflecting Pool. How long will it last? asked Kelsey, and Old Abe, grimacing in his chair, made no reply. After about 15 minutes, the thunderstorm eased into a light drizzle. I think it’s passing, I said. Let’s make a run for it. So before anyone else dared budge we galloped down the steps and we hadn’t gone a hundred yards before the rain came down like gangbusters again; the clouds rumbled, lightening flashed! Man, cold rain! The ground erupted into spongy mud and we held hands, dad and daughter, and Kelsey giggled and splashed as we waded through a puddle up to her knees. By the time we’d finished our merry run across the Mall to Union Station, we were soaked to the very marrow of our bones. The colors on her t-shirt had run down Kelsey’s belly, to her delight, and we feasted on hot cocoa and steaming baked potatoes with butter in the train station food court. Then we rushed to our hotel and took scalding showers. All the while we laughed and recounted the great adventure, our foolish folly, and to this day Kelsey’s face brightens like a beacon when telling the tale of getting caught in the rain at the Lincoln Memorial on the best trip we ever took together.*

*On the other hand, if by umbrella you mean taking steps to sustain a livable planet, protect human rights and secure a decent chance at prosperity and happiness for future generations, then let’s pack an umbrella and to heck with spontaneity.

@ @ @

(page 15) She started her new life as I drove away, and I started mine.*

*It was an emotional time for both of us, a stepping into separate voids, separate futures. To my surprise, that ripping-away emotion remained strong when I brought her and her growing, cord-tangled load of stuff to college for her sophomore and then junior years. Kelsey, though, had no such issues. College had become another home for her, a bastion of friendships and circumscribed challenges, and I’m glad of that. By the end of August, she’s primed to get back to school. But the moment we lug the final stash of coats and blankets and sheets (were these washed?) up the echoing stairwell and into her dorm room, must she really give the old man the bum’s rush? Sigh, she must.*

*My daughter is now 26 and lives in a city 600 miles away. We see each other two or three times a year and speak on the phone every weekend. She won’t friend me on Facebook. This is normal, I’m told. But I wonder, as I take care of my elderly mother in a nearby nursing home, if Kelsey will be around for me – in person, physically, -- when I’m old and infirm and repeating stories about that time we got caught in the Abe Lincoln rain. Will the cord between father and daughter, now frayed, come undone?

@ @ @

(page 19) The fuzziest one, knitted and blue, came down from my sister Suzanne. She wore it when she was an only child (like Kelsey) in the 1950s, before a torrent of siblings smothered her teenage years.*

*Suzanne says she was “intrigued by the idea of a large family” – until it actually occurred and then the reality wasn’t so hot. Her fascination was sparked by Margaret Sydney’s Five Little Peppers books; the first in the series, The Five Little Peppers and How They Grew, appeared in 1881. The Peppers lived in “a little brown house,” and led surprisingly fun and action-packed lives for the staid Victorian era. I got my picture of fake family life from reading The Happy Hollisters, who stumbled over mysterious packages and eccentric cousins at an alarming rate, while Kelsey embraced the homey life of Hobbits in The Lord of Rings trilogy.*

*Isn’t it sublime, every now and then, to be caught in the rain? When she was ten years-old, my daughter Kelsey and I took a trip to Washington, D.C. Without checking the weather forecast one morning – this being that long-ago, misty era before GPS-enabled smartphone news alerts – we walked down the Mall to the Lincoln Memorial. Once inside, as we read the marble-chiseled words of the Gettysburg Address in the great man’s shadow, the heavens split open and, boy, did it ever rain. We stood with four score or so people on the lip of the monument, looking with Lincoln at the water bounding off the surface of the Reflecting Pool. How long will it last? asked Kelsey, and Old Abe, grimacing in his chair, made no reply. After about 15 minutes, the thunderstorm eased into a light drizzle. I think it’s passing, I said. Let’s make a run for it. So before anyone else dared budge we galloped down the steps and we hadn’t gone a hundred yards before the rain came down like gangbusters again; the clouds rumbled, lightening flashed! Man, cold rain! The ground erupted into spongy mud and we held hands, dad and daughter, and Kelsey giggled and splashed as we waded through a puddle up to her knees. By the time we’d finished our merry run across the Mall to Union Station, we were soaked to the very marrow of our bones. The colors on her t-shirt had run down Kelsey’s belly, to her delight, and we feasted on hot cocoa and steaming baked potatoes with butter in the train station food court. Then we rushed to our hotel and took scalding showers. All the while we laughed and recounted the great adventure, our foolish folly, and to this day Kelsey’s face brightens like a beacon when telling the tale of getting caught in the rain at the Lincoln Memorial on the best trip we ever took together.*

*On the other hand, if by umbrella you mean taking steps to sustain a livable planet, protect human rights and secure a decent chance at prosperity and happiness for future generations, then let’s pack an umbrella and to heck with spontaneity.

@ @ @

(page 15) She started her new life as I drove away, and I started mine.*

*It was an emotional time for both of us, a stepping into separate voids, separate futures. To my surprise, that ripping-away emotion remained strong when I brought her and her growing, cord-tangled load of stuff to college for her sophomore and then junior years. Kelsey, though, had no such issues. College had become another home for her, a bastion of friendships and circumscribed challenges, and I’m glad of that. By the end of August, she’s primed to get back to school. But the moment we lug the final stash of coats and blankets and sheets (were these washed?) up the echoing stairwell and into her dorm room, must she really give the old man the bum’s rush? Sigh, she must.*

*My daughter is now 26 and lives in a city 600 miles away. We see each other two or three times a year and speak on the phone every weekend. She won’t friend me on Facebook. This is normal, I’m told. But I wonder, as I take care of my elderly mother in a nearby nursing home, if Kelsey will be around for me – in person, physically, -- when I’m old and infirm and repeating stories about that time we got caught in the Abe Lincoln rain. Will the cord between father and daughter, now frayed, come undone?

@ @ @

(page 19) The fuzziest one, knitted and blue, came down from my sister Suzanne. She wore it when she was an only child (like Kelsey) in the 1950s, before a torrent of siblings smothered her teenage years.*

*Suzanne says she was “intrigued by the idea of a large family” – until it actually occurred and then the reality wasn’t so hot. Her fascination was sparked by Margaret Sydney’s Five Little Peppers books; the first in the series, The Five Little Peppers and How They Grew, appeared in 1881. The Peppers lived in “a little brown house,” and led surprisingly fun and action-packed lives for the staid Victorian era. I got my picture of fake family life from reading The Happy Hollisters, who stumbled over mysterious packages and eccentric cousins at an alarming rate, while Kelsey embraced the homey life of Hobbits in The Lord of Rings trilogy.*

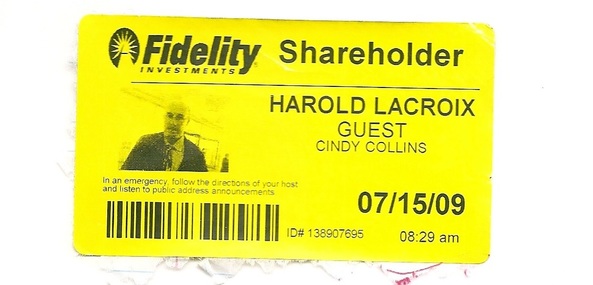

*My sister Suzanne never had kids of her own – is this how families die out, when grown children shy from the “big family” model of their Catholic parents and produce few grandchildren or none at all? My four siblings and I in the LaCroix family have borne six grandchildren, and only one is a boy carrying the Name. A lot of pressure for young Christopher who, egad, time flies at supersonic speeds, isn’t so young anymore and better get cracking or his father, desperate for direct descendants to fill up the many, many bedrooms in his Cape Cod vacation mansion, may have to start cloning.

@ @ @

(page 28) My god, the things she carried in her dorm room! One person! About now there’s 6.75 billion of us and counting toward seven billion (the big day comes in February, 2012), then eight, then nine, and finally it levels off at 9.2 billion in 2050.*

*UN population projections cite 9.2 billion as the likely middle course. If fertility rates take a dive, however, the number could level off at 8 billion in 2050, and if expected decreases in baby making don’t occur, get ready for a 2050 with 10.5 billion folks. I’m personally responsible (with her mother) for one additional human being, and I’m also the only parent in my extended family to opt for one kid. Why only one? It wasn’t a matter of ideology and we could have afforded it; Kelsey was simply enough; she was so wonderful that having another child seemed redundant, even pointless. Besides, why push your luck? Actually there’s more to it: I didn’t particularly enjoy having brothers and sisters. In fact, I found them a source of pain and anxiety. I don’t blame them – our family was twisted in knots by an abusive, alcoholic father and by the secrecy woven around that – but to this day I wrestle with brother/sister issues. Hence I “deprived” Kelsey of a sibling to spare her the trouble – but of course there’s more to it. My wife at the time was calibrating her next move. Her motivations were a mystery then, but not so much now: she felt that sharing one child, rather than two or more, was a manageable scenario for a possible future without me as her husband.*

*Whoops – UN population projections now cite 9.7 billion as the likely middle course for 2050, and what’s another 500 million hungry souls? India will easily pass China as the most populated country and plucky Nigeria, where birth control appears to be a tall tale, will double its population and jump past the U.S. into third place. Then there will be 400 million Nigerians, give or take. Capital: Lagos. Lots of oil. Muslims mostly, poor. West coast of Africa (I think). Good national soccer team. Sadly, that’s all I know.

@ @ @

(page 31) In the car* we talked about movies we’d like to see before she started her summer job in her mother’s city.

*I have since traded in my Honda for…nothing. Actually, I donated it to the Kidney Foundation and took to riding the subway and using ZipCar, a car-sharing service run through the Internet. Getting rid of my faithful car wasn’t easy, let me tell you; it was my third car and my favorite, and for years I had driven it back and forth to New Hampshire to pick up my daughter at her mother’s house where she spent most weekends of her childhood. I made the three-hour round trip about 475 times. Maybe it was the winding roads, the engine’s thrum, or the enforced proximity, but we had the best Sunday afternoon conversations in that car, long chats about her teachers and Star Trek and books and cartoons and clothes and the terrible, awful thing her whiny stepsister said, and I’d tell stories about her grandmother and uncles and aunts, about my childhood. We always played Twenty Questions. There were times, too, when she cried so hard about some sadness weighing on her soul that I had to pull the car over and rub her back as the sobs slowly, slowly subsided. Once the muffler just about fell off in a snowstorm and I used a coat hanger in the trunk to tie it back up. I slid under the car to do the job and Kelsey held tightly onto my ankle. These Sundays were our mutual flip-turns as we went back to our lives as father and daughter against the world. So you can see why it was hard letting that good car go and equally strange to become an American who does not own a car, who doesn’t possess a massive slab of steel and plastic rolling on rubber, who has extricated himself from the system of perpetual vehicle ownership that is good enough for everyone else in the country except for bums, hippies, and liberal eccentrics. The tow truck arrived around 10 a.m.; I heard it growling in the driveway while I pulled on pants and sneakers. As the driver winched my Honda’s worn tires into the air and ran those mysterious chains around the axles, I asked him what would happen next. Would my car be sold for scrap? Probably not, he said. But it failed inspection, I explained, its gaskets are torn, its manifold cracked. “Doesn’t matter,” he replied, “someone will fix it.” “Where will it go?” “Anywhere.” “You mean out of the country?” “Sure, Haiti, South America, anywhere in the world.” “Africa?” “Why not?” Then I told him: “I drove her 15 years.” A patient fellow, he smiled and slapped his palm on the dented, rusty hood. “Someone might drive her another fifteen.” I touched the hood, too, but gently, and there I was a minute later standing in the middle of the road waving goodbye to my car. I mouthed “thank you” and felt like I was gonna cry if I didn’t run inside.*

*Wouldn’t you know, just last week I donated another car to the Kidney Foundation, this one the 1993 Toyota Corolla that we acquired when Elahna’s mother, Hadassah, stopped driving. She’s since died, just checked out suddenly, dare I say a bit rudely as her brisk departure gave us no time to say goodbye while she was conscious. What she heard or misheard in the Intensive Care Unit will remain a mystery for the foreseeable future. Did she even feel our hands holding hers? So, anyway, I had grown to like her old car but the high cost of repairs was getting ridiculous. So we disposed of it – you know, when an elderly person dies it’s as if you keep burying her for months and months: estate and probate issues, packing and unpacking of possessions, surreal hospital and ambulance bills, picking out the gravestone with just the right Hebrew saying. And so on. And what to do on Passover without her? On her birthday? And how to divert the prodigious flood of shoe, coat, gardening and archeological tour catalogs that our mailman with the enormous calves hauls up our walk? We’ve since replaced her Toyota with an all-electric BMW i3, built in a green factory and powered by the solar panels on our roof. Hadassah, who grew up in Jerusalem during Israel’s War of Independence, would never have bought a German car, but I’m glad we did. Sooner or later, you have to forgive.

@ @ @

(page 36) Ninety countries earned the free ranking from Freedom House, ten more countries than were found to be democratic by the Economist’s reckoning. Sixty countries were judged as partly free and 43 as not free. A merging of the two indices reveals that about half the world’s population is denied human rights.*

*It’s hard to look at an individual human being and understand why that person should be denied freedom. One day last summer, Kelsey and I were sitting on the back porch and I looked up at her and marveled. She was reading a novel, unaware of my scrutiny, her head slightly cocked, her blonde hair spilling toward the pages, and the expression on her face was relaxed but absorbed; she glowed in the late afternoon sunshine. For that moment she seemed absolutely comfortable in her skin and it was as if my daughter’s potential as a human being had quietly surfaced, as if I had seen through a window into her best possible future. As if I had heard an echo of good things to come. Portrait of Kelsey on Porch – it’s the image of her I carry in my head. (Often, though, I still think of her as a skipping, crying little girl. She kept tra-la-la skipping long after her classmates stopped; she cried prodigiously, in great gulping gasps.) In the Prado museum in Madrid, there’s a self portrait by the artist Durer, painted in 1498. I looked at him long and hard one day, as Spanish and English words floated around me, and he stared back haughty and unwavering, proclaiming I Am, I Will Be across 512 years, across the Age of Enlightenment and all the wars and revolutions and near apocalypses that followed. Like I said, it’s hard to look at an individual human being and understand why that person should be denied freedom.*

*In its 2016 report, Freedom House notes another bad year for global freedom, which has been on the decline for ten years. Seventy-two countries declined in freedom last year; 43 showed improvement. This has occurred simultaneously with the rise of the Internet and its emphasis on individual expression through social media. Do we have a paradox here? As for my daughter, I remain ever hopeful that her best possible future will come to pass despite the travails and challenges of life in this fractious century.

@ @ @

(page 54) W. Warren Wagar, the preeminent scholar on H.G. Wells, received a jolt of publicity in 1983 from an Associated Press article about his History of World War III course. The story focused on the professor’s worries about nuclear war,* but also included his belief that any of four developments could avert catastrophe: disarmament, world government, an international order led by multinational corporations, and the rise of a “technological community” that takes over the key functions of government.

*Wagar was no doomsday peddler, nor were his Reagan-era students. In a survey he gave his classes in 1983, only 10 percent felt that the world would destroy itself, a marked change from the 30 percent who felt we were gonzo during the frugal reign of Jimmy Carter, just one year before. Besides, doomsday isn’t always that bad in the end. Wager’s book Terminal Visions: The Literature of Last Things notes that more than 80 percent of the 350 end-time stories he researched ushered in an era of transformation and renewal. (It’s the getting there that hurts, all those trials and tribulations.) If Wagar waxed pessimistic in 1983, we might recall that the Cold War hit a hysterical peak in that year. January: millions march, including yours truly during a semester abroad in London, in opposition to President Reagan’s plan to deploy more nuclear missiles in Western Europe. March: Reagan labels the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” and accelerates research on a space-based “Star Wars” defense shield against a nuclear first strike. April: eleven year-old Samantha Smith of Houlton, Maine, writes Soviet leader Yuri Andropov and asks him, “Are you going to vote to have a war or not?” June: Andropov, who as KGB chief savagely repressed the Hungarian uprising of 1956 and the Prague Spring of 1968, writes cloying letter to Samantha comparing her to Becky Thatcher in Tom Sawyer. July: Samantha visits Soviet Union and tells world that Soviet citizens are “just like us,” but her meeting with Andropov is canceled. September: Soviet jets shoot down Korean Air Lines Flight 007, killing 269 people including a U.S. congressman. October: tens of millions read, including yours truly at his mother’s kitchen table, article in Parade magazine by Carl Sagan describing horrors of globe-enshrouding “nuclear winter” that could result from a nuclear “exchange.” November: 100 million plus Americans grow communally terrified, once more including yours truly, as they watch The Day After, a TV movie depicting nuclear Armageddon in excruciating detail. It was a freaky year. Andropov is dead by February 1984 and, sadly, the remarkable Samantha Smith, who had written a book on her adventures and starred in a TV series as the precocious daughter of an international sophisticate, was killed in a plane crash the following August. Emotional messages were sent to her funeral by President Reagan and Soviet leader Michael Gorbachev, whose partnership would engineer a peaceful end to the Cold War, and who’s to say the world wouldn’t have turned out differently but for little Samantha Smith, a butterfly whose wings beat strongly, and who can’t forgive William Wagar for despairing of man’s fate, now and then, with all that crazy stuff going on in 1983?*

*It only occurred to me yesterday – ever late my brain blooms – that my fascination with the year 1983 bumps up against my love of George Orwell’s novel 1984. In that crazy year of schoolgirl peaceniks and looming Armageddon, did some people believe that we were headed into some kind of Orwellian dead zone – as soon as the next year?

@ @ @

(page 66) Don’t look for a politician to lead the cause, Paul Raskin insists, but someone along the lines of Martin Luther King or Mahatma Gandhi. Hmmm, sounds like a tall order.*

* The closest thing now to a Global Citizens Movement is something called the World Social Forum, which held its 2009 summit in Belem, Brazil. Over 100,000 activists attended and I’m sure that most of them are idealistic, kind, and striving to help the downtrodden, right wrongs, and keep the world from spiraling into the Barbarization era. But it’s disturbing to read that Venezuelan petro-dictator Hugo Chavez got a rousing welcome there, and it’s very disturbing to see the inclusion of anarchist and extremist groups, many of whom blame Jews for the excesses of capitalism and reflexively malign Israel. If this “diverse” gang is the Global Citizens Movement that will someday rescue the planet and bring about a fab future for mankind, count me out. I’d rather charge up the down escalator with the Policy Reform fools. Call me stubborn. (Kelsey tells me to relax; her generation is way too materialistic and hooked into pop culture to demand big changes; maybe the next generation, she says. Maybe I caught her on a bad day.)*

*Well, now in 2016 we also have the global youth brigade of 350.org battling climate change and the fervent young folks championing Bernie Sanders’ political revolution that came up short against policy-reformer Hilary Clinton. Maybe the whole rotten apple cart will finally be toppled, burned…and here comes a raging, worldwide fever for a smartphone video game called Pokémon Go and what’s that you were saying?

@ @ @

(page 28) My god, the things she carried in her dorm room! One person! About now there’s 6.75 billion of us and counting toward seven billion (the big day comes in February, 2012), then eight, then nine, and finally it levels off at 9.2 billion in 2050.*

*UN population projections cite 9.2 billion as the likely middle course. If fertility rates take a dive, however, the number could level off at 8 billion in 2050, and if expected decreases in baby making don’t occur, get ready for a 2050 with 10.5 billion folks. I’m personally responsible (with her mother) for one additional human being, and I’m also the only parent in my extended family to opt for one kid. Why only one? It wasn’t a matter of ideology and we could have afforded it; Kelsey was simply enough; she was so wonderful that having another child seemed redundant, even pointless. Besides, why push your luck? Actually there’s more to it: I didn’t particularly enjoy having brothers and sisters. In fact, I found them a source of pain and anxiety. I don’t blame them – our family was twisted in knots by an abusive, alcoholic father and by the secrecy woven around that – but to this day I wrestle with brother/sister issues. Hence I “deprived” Kelsey of a sibling to spare her the trouble – but of course there’s more to it. My wife at the time was calibrating her next move. Her motivations were a mystery then, but not so much now: she felt that sharing one child, rather than two or more, was a manageable scenario for a possible future without me as her husband.*

*Whoops – UN population projections now cite 9.7 billion as the likely middle course for 2050, and what’s another 500 million hungry souls? India will easily pass China as the most populated country and plucky Nigeria, where birth control appears to be a tall tale, will double its population and jump past the U.S. into third place. Then there will be 400 million Nigerians, give or take. Capital: Lagos. Lots of oil. Muslims mostly, poor. West coast of Africa (I think). Good national soccer team. Sadly, that’s all I know.

@ @ @

(page 31) In the car* we talked about movies we’d like to see before she started her summer job in her mother’s city.

*I have since traded in my Honda for…nothing. Actually, I donated it to the Kidney Foundation and took to riding the subway and using ZipCar, a car-sharing service run through the Internet. Getting rid of my faithful car wasn’t easy, let me tell you; it was my third car and my favorite, and for years I had driven it back and forth to New Hampshire to pick up my daughter at her mother’s house where she spent most weekends of her childhood. I made the three-hour round trip about 475 times. Maybe it was the winding roads, the engine’s thrum, or the enforced proximity, but we had the best Sunday afternoon conversations in that car, long chats about her teachers and Star Trek and books and cartoons and clothes and the terrible, awful thing her whiny stepsister said, and I’d tell stories about her grandmother and uncles and aunts, about my childhood. We always played Twenty Questions. There were times, too, when she cried so hard about some sadness weighing on her soul that I had to pull the car over and rub her back as the sobs slowly, slowly subsided. Once the muffler just about fell off in a snowstorm and I used a coat hanger in the trunk to tie it back up. I slid under the car to do the job and Kelsey held tightly onto my ankle. These Sundays were our mutual flip-turns as we went back to our lives as father and daughter against the world. So you can see why it was hard letting that good car go and equally strange to become an American who does not own a car, who doesn’t possess a massive slab of steel and plastic rolling on rubber, who has extricated himself from the system of perpetual vehicle ownership that is good enough for everyone else in the country except for bums, hippies, and liberal eccentrics. The tow truck arrived around 10 a.m.; I heard it growling in the driveway while I pulled on pants and sneakers. As the driver winched my Honda’s worn tires into the air and ran those mysterious chains around the axles, I asked him what would happen next. Would my car be sold for scrap? Probably not, he said. But it failed inspection, I explained, its gaskets are torn, its manifold cracked. “Doesn’t matter,” he replied, “someone will fix it.” “Where will it go?” “Anywhere.” “You mean out of the country?” “Sure, Haiti, South America, anywhere in the world.” “Africa?” “Why not?” Then I told him: “I drove her 15 years.” A patient fellow, he smiled and slapped his palm on the dented, rusty hood. “Someone might drive her another fifteen.” I touched the hood, too, but gently, and there I was a minute later standing in the middle of the road waving goodbye to my car. I mouthed “thank you” and felt like I was gonna cry if I didn’t run inside.*

*Wouldn’t you know, just last week I donated another car to the Kidney Foundation, this one the 1993 Toyota Corolla that we acquired when Elahna’s mother, Hadassah, stopped driving. She’s since died, just checked out suddenly, dare I say a bit rudely as her brisk departure gave us no time to say goodbye while she was conscious. What she heard or misheard in the Intensive Care Unit will remain a mystery for the foreseeable future. Did she even feel our hands holding hers? So, anyway, I had grown to like her old car but the high cost of repairs was getting ridiculous. So we disposed of it – you know, when an elderly person dies it’s as if you keep burying her for months and months: estate and probate issues, packing and unpacking of possessions, surreal hospital and ambulance bills, picking out the gravestone with just the right Hebrew saying. And so on. And what to do on Passover without her? On her birthday? And how to divert the prodigious flood of shoe, coat, gardening and archeological tour catalogs that our mailman with the enormous calves hauls up our walk? We’ve since replaced her Toyota with an all-electric BMW i3, built in a green factory and powered by the solar panels on our roof. Hadassah, who grew up in Jerusalem during Israel’s War of Independence, would never have bought a German car, but I’m glad we did. Sooner or later, you have to forgive.

@ @ @

(page 36) Ninety countries earned the free ranking from Freedom House, ten more countries than were found to be democratic by the Economist’s reckoning. Sixty countries were judged as partly free and 43 as not free. A merging of the two indices reveals that about half the world’s population is denied human rights.*

*It’s hard to look at an individual human being and understand why that person should be denied freedom. One day last summer, Kelsey and I were sitting on the back porch and I looked up at her and marveled. She was reading a novel, unaware of my scrutiny, her head slightly cocked, her blonde hair spilling toward the pages, and the expression on her face was relaxed but absorbed; she glowed in the late afternoon sunshine. For that moment she seemed absolutely comfortable in her skin and it was as if my daughter’s potential as a human being had quietly surfaced, as if I had seen through a window into her best possible future. As if I had heard an echo of good things to come. Portrait of Kelsey on Porch – it’s the image of her I carry in my head. (Often, though, I still think of her as a skipping, crying little girl. She kept tra-la-la skipping long after her classmates stopped; she cried prodigiously, in great gulping gasps.) In the Prado museum in Madrid, there’s a self portrait by the artist Durer, painted in 1498. I looked at him long and hard one day, as Spanish and English words floated around me, and he stared back haughty and unwavering, proclaiming I Am, I Will Be across 512 years, across the Age of Enlightenment and all the wars and revolutions and near apocalypses that followed. Like I said, it’s hard to look at an individual human being and understand why that person should be denied freedom.*

*In its 2016 report, Freedom House notes another bad year for global freedom, which has been on the decline for ten years. Seventy-two countries declined in freedom last year; 43 showed improvement. This has occurred simultaneously with the rise of the Internet and its emphasis on individual expression through social media. Do we have a paradox here? As for my daughter, I remain ever hopeful that her best possible future will come to pass despite the travails and challenges of life in this fractious century.

@ @ @

(page 54) W. Warren Wagar, the preeminent scholar on H.G. Wells, received a jolt of publicity in 1983 from an Associated Press article about his History of World War III course. The story focused on the professor’s worries about nuclear war,* but also included his belief that any of four developments could avert catastrophe: disarmament, world government, an international order led by multinational corporations, and the rise of a “technological community” that takes over the key functions of government.

*Wagar was no doomsday peddler, nor were his Reagan-era students. In a survey he gave his classes in 1983, only 10 percent felt that the world would destroy itself, a marked change from the 30 percent who felt we were gonzo during the frugal reign of Jimmy Carter, just one year before. Besides, doomsday isn’t always that bad in the end. Wager’s book Terminal Visions: The Literature of Last Things notes that more than 80 percent of the 350 end-time stories he researched ushered in an era of transformation and renewal. (It’s the getting there that hurts, all those trials and tribulations.) If Wagar waxed pessimistic in 1983, we might recall that the Cold War hit a hysterical peak in that year. January: millions march, including yours truly during a semester abroad in London, in opposition to President Reagan’s plan to deploy more nuclear missiles in Western Europe. March: Reagan labels the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” and accelerates research on a space-based “Star Wars” defense shield against a nuclear first strike. April: eleven year-old Samantha Smith of Houlton, Maine, writes Soviet leader Yuri Andropov and asks him, “Are you going to vote to have a war or not?” June: Andropov, who as KGB chief savagely repressed the Hungarian uprising of 1956 and the Prague Spring of 1968, writes cloying letter to Samantha comparing her to Becky Thatcher in Tom Sawyer. July: Samantha visits Soviet Union and tells world that Soviet citizens are “just like us,” but her meeting with Andropov is canceled. September: Soviet jets shoot down Korean Air Lines Flight 007, killing 269 people including a U.S. congressman. October: tens of millions read, including yours truly at his mother’s kitchen table, article in Parade magazine by Carl Sagan describing horrors of globe-enshrouding “nuclear winter” that could result from a nuclear “exchange.” November: 100 million plus Americans grow communally terrified, once more including yours truly, as they watch The Day After, a TV movie depicting nuclear Armageddon in excruciating detail. It was a freaky year. Andropov is dead by February 1984 and, sadly, the remarkable Samantha Smith, who had written a book on her adventures and starred in a TV series as the precocious daughter of an international sophisticate, was killed in a plane crash the following August. Emotional messages were sent to her funeral by President Reagan and Soviet leader Michael Gorbachev, whose partnership would engineer a peaceful end to the Cold War, and who’s to say the world wouldn’t have turned out differently but for little Samantha Smith, a butterfly whose wings beat strongly, and who can’t forgive William Wagar for despairing of man’s fate, now and then, with all that crazy stuff going on in 1983?*

*It only occurred to me yesterday – ever late my brain blooms – that my fascination with the year 1983 bumps up against my love of George Orwell’s novel 1984. In that crazy year of schoolgirl peaceniks and looming Armageddon, did some people believe that we were headed into some kind of Orwellian dead zone – as soon as the next year?

@ @ @

(page 66) Don’t look for a politician to lead the cause, Paul Raskin insists, but someone along the lines of Martin Luther King or Mahatma Gandhi. Hmmm, sounds like a tall order.*

* The closest thing now to a Global Citizens Movement is something called the World Social Forum, which held its 2009 summit in Belem, Brazil. Over 100,000 activists attended and I’m sure that most of them are idealistic, kind, and striving to help the downtrodden, right wrongs, and keep the world from spiraling into the Barbarization era. But it’s disturbing to read that Venezuelan petro-dictator Hugo Chavez got a rousing welcome there, and it’s very disturbing to see the inclusion of anarchist and extremist groups, many of whom blame Jews for the excesses of capitalism and reflexively malign Israel. If this “diverse” gang is the Global Citizens Movement that will someday rescue the planet and bring about a fab future for mankind, count me out. I’d rather charge up the down escalator with the Policy Reform fools. Call me stubborn. (Kelsey tells me to relax; her generation is way too materialistic and hooked into pop culture to demand big changes; maybe the next generation, she says. Maybe I caught her on a bad day.)*

*Well, now in 2016 we also have the global youth brigade of 350.org battling climate change and the fervent young folks championing Bernie Sanders’ political revolution that came up short against policy-reformer Hilary Clinton. Maybe the whole rotten apple cart will finally be toppled, burned…and here comes a raging, worldwide fever for a smartphone video game called Pokémon Go and what’s that you were saying?

@ @ @

(page 69) In 2030, tiny Belize will be inundated with millions of refugees.*

*Until that crisis, Belize had managed to remain one of the most delightful and remote countries in the world. As Aldous Huxley said when he visited in 1934, Belize is “not on the way to anywhere from anywhere else.” He said that in a snotty way, alas, wondering why the British Empire bothered with keeping it, especially since the chief Belizean export, mahogany, was no longer the preferred wood for an English dining table. When I visited there in 2010, Belize had a population density of 36 people per square mile; compare that to 83 per square mile in the U.S. (including Alaska!), 334 per square mile in Guatemala, and 877 per in Israel. It was a young country then with half the population under the age of 20 and I often think of a little Belizean girl in a pink, frilly dress we spied as we bumped along the rutted, red-clay road leading to the Five Sisters Lodge in the rainforest. It was a cinematic image, something out of an old Western: our van turned the corner and there she was, the little girl, maybe seven years old and running in bare feet from the door of her small house roofed in tin and thatch to the fence at the edge of the road, waving happily, waving at us, the eco-tourists from Los Estados Unidos. Elahna waved back. The girl’s frilly dress was the pinkest thing I’ve ever seen, pink beyond imagining against her black skin, and I think I saw chickens in her wake and a little brother – though my mind could have supplied those details. We passed one car during our hour’s drive on that road and I wonder how many times a day the girl in pink ran like crazy from her stoop to wave at a passing vehicle. Was she just fooling around, bored? Or was it the highlight of her day – to see the people from far away go by, to show off her beautiful dress – and I wonder, too, what happened to the grown woman who was once that little girl. Is she alive? Does she still wear pink?*

*Okay, enough with the 2030 look back. In real time, that little girl is now thirteen or fourteen, and it’s not easy being an adolescent anywhere in the world. Let’s hope she’s getting a good education. She’s gonna need it as I read that average no longer cuts it in this ultracompetitive, globalized economy, and btw, mahogany remains out of fashion as furniture. Confirmation: unfashionable me owns several sturdy pieces.

@ @ @

(page 72) If nothing else I’ve built into my system the sustaining belief that my next job/ destination/adventure will be fantastic or at least worth the effort. I’ve learned to recover from failure and make myself anew.*

* Several times my sister Suzanne has told me the story of the enormous, abandoned aloe plant – and let me state first that I believe people repeat stories, even stray ones about aloe plants, because they have profound meaning in their lives. In one version of the aloe tale, it’s discovered in a pile of dirt by the side of the road; in another, Suzanne finds it dumped in the back of her brother-in-law’s pickup truck, root ball and all. At any rate, she takes the hulking aloe home and plants it in the fertile soil of her garden, giving it extra doses of nitrogen, water, and love. But the darn thing goes limp and fades, its bright green spears turning dark in the Florida sun. Despite her kind ministrations, the aloe is dying. Brown juice oozes like pus from erupting seams in the plant’s skin. All right, says Suzanne, no more Ms. Nice Gal! She marches to a nearby construction site, scoops up a load of the worst, sandiest soil on Earth plentifully poisoned with toxic debris, and returns to her yard. She yanks up the orphan aloe, mixes the garbage soil into the ground, and shoves the plant right in there: eat that, buster! And drink rainwater, no more special concoction for you! Well, wouldn’t you know it, the aloe soon it regains its green glow, metastasizing a tangle of new, mutant branches. In adversity, life blooms.*

*Yes, I agree, but let’s not make a cult of this observation Some plants and people and places and traditions infused with wisdom and passed down from generation to generation require nurturing, need a good bit of clucking over. Another thing I have come to know: as you age, it gets much harder to make one’s self anew. So it’s best not to chance the transition too many times before time and odds catch up with you.

@ @ @

(page 83) Contrary to the propaganda of the Goodyear Corporation, the Olmec people of Mesoamerica invented vulcanized rubber over a thousand years ago using the juice of the morning glory as a catalytic agent.*

*I grow a pot of morning glories on my back porch. Slowly, surely they entangle and ascend a huge trellis screwed to the house, putting out one or two blue blooms per night in early summer and then accelerating the output until 20-25 blooms of blue and purple and white, and blue streaked with veins of purple, explode nightly in September and early October. Is this a homegrown metaphor, acceleration of change photosynthesized, and if so are we approaching the autumn of our days? Has Mankind stumbled into mid-life, with its high productivity and creeping anxieties, its blooming crises? Soon, of course, the morning glory blooms of October flag and come less profusely, then not at all, and the leaves hang limp and brown. And so I collect hard, black seeds from its pods for the spring crop and harvest the plant’s limbic juice for making a rubber ball to throw against a wall, ba-doom, ba-doom, all winter long.*

*I’ve continued to harvest morning glory seeds every fall and replant them in the spring, producing blooms with direct ancestors going back ten years now. Over time, though, the color diversity of blooms has narrowed for complicated genetic reasons, and I have the impression that the plants don’t climb up trellises as aggressively, but that may be due to the partial shadiness of the backyard at our new house. Nonetheless, perhaps next year I’ll introduce some immigrant, even refugee seeds into the mix…

(page 69) In 2030, tiny Belize will be inundated with millions of refugees.*

*Until that crisis, Belize had managed to remain one of the most delightful and remote countries in the world. As Aldous Huxley said when he visited in 1934, Belize is “not on the way to anywhere from anywhere else.” He said that in a snotty way, alas, wondering why the British Empire bothered with keeping it, especially since the chief Belizean export, mahogany, was no longer the preferred wood for an English dining table. When I visited there in 2010, Belize had a population density of 36 people per square mile; compare that to 83 per square mile in the U.S. (including Alaska!), 334 per square mile in Guatemala, and 877 per in Israel. It was a young country then with half the population under the age of 20 and I often think of a little Belizean girl in a pink, frilly dress we spied as we bumped along the rutted, red-clay road leading to the Five Sisters Lodge in the rainforest. It was a cinematic image, something out of an old Western: our van turned the corner and there she was, the little girl, maybe seven years old and running in bare feet from the door of her small house roofed in tin and thatch to the fence at the edge of the road, waving happily, waving at us, the eco-tourists from Los Estados Unidos. Elahna waved back. The girl’s frilly dress was the pinkest thing I’ve ever seen, pink beyond imagining against her black skin, and I think I saw chickens in her wake and a little brother – though my mind could have supplied those details. We passed one car during our hour’s drive on that road and I wonder how many times a day the girl in pink ran like crazy from her stoop to wave at a passing vehicle. Was she just fooling around, bored? Or was it the highlight of her day – to see the people from far away go by, to show off her beautiful dress – and I wonder, too, what happened to the grown woman who was once that little girl. Is she alive? Does she still wear pink?*

*Okay, enough with the 2030 look back. In real time, that little girl is now thirteen or fourteen, and it’s not easy being an adolescent anywhere in the world. Let’s hope she’s getting a good education. She’s gonna need it as I read that average no longer cuts it in this ultracompetitive, globalized economy, and btw, mahogany remains out of fashion as furniture. Confirmation: unfashionable me owns several sturdy pieces.

@ @ @

(page 72) If nothing else I’ve built into my system the sustaining belief that my next job/ destination/adventure will be fantastic or at least worth the effort. I’ve learned to recover from failure and make myself anew.*

* Several times my sister Suzanne has told me the story of the enormous, abandoned aloe plant – and let me state first that I believe people repeat stories, even stray ones about aloe plants, because they have profound meaning in their lives. In one version of the aloe tale, it’s discovered in a pile of dirt by the side of the road; in another, Suzanne finds it dumped in the back of her brother-in-law’s pickup truck, root ball and all. At any rate, she takes the hulking aloe home and plants it in the fertile soil of her garden, giving it extra doses of nitrogen, water, and love. But the darn thing goes limp and fades, its bright green spears turning dark in the Florida sun. Despite her kind ministrations, the aloe is dying. Brown juice oozes like pus from erupting seams in the plant’s skin. All right, says Suzanne, no more Ms. Nice Gal! She marches to a nearby construction site, scoops up a load of the worst, sandiest soil on Earth plentifully poisoned with toxic debris, and returns to her yard. She yanks up the orphan aloe, mixes the garbage soil into the ground, and shoves the plant right in there: eat that, buster! And drink rainwater, no more special concoction for you! Well, wouldn’t you know it, the aloe soon it regains its green glow, metastasizing a tangle of new, mutant branches. In adversity, life blooms.*

*Yes, I agree, but let’s not make a cult of this observation Some plants and people and places and traditions infused with wisdom and passed down from generation to generation require nurturing, need a good bit of clucking over. Another thing I have come to know: as you age, it gets much harder to make one’s self anew. So it’s best not to chance the transition too many times before time and odds catch up with you.

@ @ @

(page 83) Contrary to the propaganda of the Goodyear Corporation, the Olmec people of Mesoamerica invented vulcanized rubber over a thousand years ago using the juice of the morning glory as a catalytic agent.*

*I grow a pot of morning glories on my back porch. Slowly, surely they entangle and ascend a huge trellis screwed to the house, putting out one or two blue blooms per night in early summer and then accelerating the output until 20-25 blooms of blue and purple and white, and blue streaked with veins of purple, explode nightly in September and early October. Is this a homegrown metaphor, acceleration of change photosynthesized, and if so are we approaching the autumn of our days? Has Mankind stumbled into mid-life, with its high productivity and creeping anxieties, its blooming crises? Soon, of course, the morning glory blooms of October flag and come less profusely, then not at all, and the leaves hang limp and brown. And so I collect hard, black seeds from its pods for the spring crop and harvest the plant’s limbic juice for making a rubber ball to throw against a wall, ba-doom, ba-doom, all winter long.*

*I’ve continued to harvest morning glory seeds every fall and replant them in the spring, producing blooms with direct ancestors going back ten years now. Over time, though, the color diversity of blooms has narrowed for complicated genetic reasons, and I have the impression that the plants don’t climb up trellises as aggressively, but that may be due to the partial shadiness of the backyard at our new house. Nonetheless, perhaps next year I’ll introduce some immigrant, even refugee seeds into the mix…

@ @ @

(page 85) It can be argued, she says, that we’ve entered a near-plateau of technological stasis after the seminal discoveries of oil (1858), internal combustion (1860), electric light bulb (1879), radio (1893), antibiotics (1909), television (1927), electron microscope (1931), controlled nuclear fission (1945), rocketry for space travel and satellite seeding (1949), the computer chip (1953), and finally the polio vaccine (1955) and laser (1960). Those were the low-hanging fruit, easy picking. Since those breakthroughs, it’s been mostly gadgets and gizmos adept at measurement, miniaturization, and magnification*, at reshaping, reworking, and cleverly combining, at distributing far, deep, and wide.

*Oh, how our modern eyes do roam – into the switchback structures of proteins that comprise our genes, through the galactic mist to Earth-like planets around distant stars. It’s gee-whiz-bang to the nth degree, intellectually fascinating, yet such far seeing isn’t likely to change our lives for a long time. Everything’s got to have a catch, no? For instance, scientists have developed a powerful new CT scanner that detects until-now-undetectable soft plaque in arteries – a marker of “silent heart disease” which afflicts apparently healthy individuals. Problem is, this magnificent magnification, this feat of coronary sleuthing, happens to be outrageously expensive and therefore cannot be employed to screen its intended audience – healthy, middle-aged folk like me – unless its price drops one-hundred fold. Of course, rich people can always pay out of pocket.*

*Be careful what you write about. A problem heart is just a short breath, a skipped beat away, and there I was last month in Mass General Hospital’s catheterization lab, twice, getting my atria examined by amazing gizmos at the tips of catheters inserted into veins in my arm and neck. Good news: no coronary heart disease or pulmonary hypertension. Not good: dilated right ventricle and pulmonary artery caused by a congenital abnormality called an atrial septal defect (ASD). A shunt, the doctors say. Translation: there’s a hole in my heart the size of a quarter, causing trouble over time. (Toss in anomalous pulmonary veins to further complicate matters.) Surgical consult pending. An ASD is a random glitch in the body’s system, over decades sabotaging the cathedral of the heart like a patient, artisan-vandal, and it’s not an inherited defect. So I can’t really blame my parents, and there’s no evidence that the anti-miscarriage drugs my mother took had a role, despite Internet med-gossip. Why, btw, did she go to such lengths to have a fifth, anomalous child? Why risk another miscarriage? Did my mom exercise control over her future, and by extension mine, or was it dictated by her husband, the censorious church or some primal urge beyond reckoning? I guess Leonard Cohen sang it best: “There is a crack, a crack in everything/that’s how the light gets in.”

@ @ @

(page 93) The poet Samuel Coleridge got it right: “The light that experience gives us is a lantern on the stern, which shines only on the waves behind us.” Or to quote the main character in Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel, Looking Backward, written in 1887 and set in a futuristic Boston of the year 2000: “One can look back a thousand years easier than forward fifty.”*

*Nonetheless, it’s hard not to try. I’m a big fan of Peter Turchin’s War and Peace and War, with its impassioned riffs on the life cycles of imperial nations, the meta-ethnic frontiers where empires arise, and the singular quality of asabiya – “the capacity of a social group for concerted, collective action,” – without which a country cannot survive. Uh oh – that’s us. I also admire Robert Jay Lofton’s book on the Aum Shinrikyo cult responsible for the 1995 sarin gas attacks in the Tokyo subway system. Lofton believes that Japan suffers from “psychohistorical dislocation – a breakdown of the social and institutional arrangements that ordinarily anchor human lives” a syndrome in which “people experience a profound gap between what they feel themselves to be and what a society or culture expects them to be.” Analysis not restricted to Japan – uh oh, again.*

*Indeed, looking ahead is almost impossible. Ray Bradbury, among the most esteemed sci-fi writers of the 20th century, had a talent for envisioning future scenarios replete with time travel, telepathy and advanced technologies, but he could not for the life of him envision a future in which women were not primarily housewives and a bit hysterical to boot. Female presidents, CEOs, doctors, lawyers, crime lords, TV anchors, geologists – unimaginable! And so his aproned honeys bake peach crumble on Mars while the men go out to laser-vaporize floating, blue indigenous life forms. Same as it always was.

@ @ @

(page 101) The clerk at Petsi Pies, who has that shaggy, perpetual grad student aura, notices the paperback in my pocket – The Elephant Vanishes, by Haruki Murakami – and we exchange enthusiasm for his work. I remark on a story in the book about a man who burns down old barns as a hobby and the grad student shakes his head, yes, yes, he knows it, but then the door chimes and a customer approaches the bakery case, pointing at a pie. The clerk and I nod at each other, co-conspirators in the vast Murakami cult.*

*Murakami’s books have sold tens of millions of copies and are translated into more than 40 languages. There is little exotic or Japanese about them, and with a few name and detail changes his stories could take place in almost any country in the world. He is a World Author writing World Literature. Kim Choon Me, professor at Korean University, says young people in South Korea “have found in Murakami a cultural code in which they can share their own conflicts and woes, a code that perfectly speaks to them.” She continues: “The more the world grows into a late capitalist society, his novels can be expected to spread with increasing force as transnational cultural commodities.” Not hard commodities, though, like Nike sneakers or McDonald’s hamburgers or Disney plastic action figures. Murakami provides commodities of dreams, elusive and beguiling dreams shared over bakery counters and across cities and oceans and barbed-wire borders. According to Roland Kelts, author of Japanamerica, readers see in Murakami’s narratives “the tones and colors of their own dreams…something they know and feel, but maybe cannot explain.” *

*Murakami-mania has only increased with record-breaking sales of his recent novels 1Q84 and Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and his Years of Pilgrimage. The obvious terminus of this trend, if Murakami can live and write long enough, is that every reader on the planet will one day buy a copy of his latest book, making him richer than Oprah. Murakami likens writing to eating fried oysters alone and lists Raymond Chandler and Kurt Vonnegut as key influences. Speaking of Vonnegut, I once heard him on the Imus in the Morning radio show say that Hitler should be sentenced in Hell to a never-ending orgasm, and that kind of lost me and Imus, too. Also, I must admire that phrase I coined in the footnote above, “commodities of dreams.” In the great commodities market for dreams, somewhere I think in Nebraska, would you be buying or selling?

@ @ @

(page 104) Over here, Draper Labs, the Whitehead Institute, Novartis. Over there, the Broad Institute, Genzyme, the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research rising from a fenced-off square of ground. The place is booming; it’s a little China, Dubai, Singapore, Bangalore. Here, in our backyard! Oh, what elixirs for longer and better life brew about me! What potions of hope immemorial! It cheers me that Elahna, a biomedical researcher as well as a pediatrician, is part of this grand effort.*

*She called during an earlier segment of this ramble and griped about the paperwork for flying eight genetically modified mice in from London. In New York they would undergo artificial insemination and then be mailed to her lab in Boston. You know, typical female yakkity-yak. The trials and tribulations of these mutant mice were funded with a tiny, tiny portion of President Obama’s $787 billion stimulus package intended to juice the U.S. economy. It’s all part of Elahna’s quixotic quest to locate the genes that cause kidney disease – kidney disease in mice, she will add in deprecation. One day she expressed discomfort for “wasting” taxpayers’ money on a project with low odds of success and I, the ever-helpful partner, reminded her that “negative results” (failures) can inform future researchers of which dead ends to avoid. So ship those mice already!*

* Alas, Elahna never published her negative results and soon left the basic research world to focus on clinical work, so some schmuck valedictorian genius may someday go down the same research rabbit holes. We keep repeating our mistakes, individually and as a species, although the saviors of big data, artificial intelligence, augmented reality and cross-departmental mindfulness promise to sort out the great garbage mound of information, both stupid and smart. Or things might just get mucked up worse, which might not be all bad. Perhaps my wife’s experiments bore ambiguous results (flopped) because her technician forgot to stir something clockwise rather than counter-clockwise and, therefore, with proper technique and the right glint of light through the 13th floor skylight, it’ll be Eureka! Eureka! the next time around.

@ @ @

(page 111) Tenants listed include Boston Paintball, an asset recovery firm, and a substance abuse counseling center. Are paintballers in there now, warless warriors ranging across a post-industrial landscape, pattered with red, blue, green, DayGlo orange, and security-stone pink?*

*Color, is that it? Is that what makes the world of today seem so different, so achingly modern, than the world of 50-75 years ago? The bright neon colors, the endless variations of shades, some of which do not under any circumstances appear in nature. A cavalcade of colors on hats, shoes, t-shirts, cars, city buses, and airplanes, crazy Calypso colors swirling on movie, PC, and cell phone screens, power colors streaking the donated clothes of the poorest slum kids. The past was so drab, the colors muted, isn’t that the idea? No cobalt blue on Cary Grant, no avocado green on Kate Hepburn.*

*Now I can add to that list the multicolored orange and lime-green sneakers everyone’s wearing. A variation on the modern-by-color effect, as described above, occurs in contemporary historical movies. For instance, I’d seen Jesse Owen’s feats at the 1936 Berlin Olympics only in black-and-white documentary form, but the recent film Race depicts his life and track-and-field victories in vibrant color. Who knew that U.S. athletes were issued blue boutonnieres upon arrival in Nazi Germany? The red of the swastika flags, like blood. In color, it seems as if it all happened yesterday. Semi-brilliant idea: add modern conveniences to films set in the past – swap guns for swords, iPhones for black rotary jobs, luminescent yellow Nikes for Jessie’s handmade Adi Dassler spikes – and time itself will be obliterated. Everything and everywhen will be now.

(page 85) It can be argued, she says, that we’ve entered a near-plateau of technological stasis after the seminal discoveries of oil (1858), internal combustion (1860), electric light bulb (1879), radio (1893), antibiotics (1909), television (1927), electron microscope (1931), controlled nuclear fission (1945), rocketry for space travel and satellite seeding (1949), the computer chip (1953), and finally the polio vaccine (1955) and laser (1960). Those were the low-hanging fruit, easy picking. Since those breakthroughs, it’s been mostly gadgets and gizmos adept at measurement, miniaturization, and magnification*, at reshaping, reworking, and cleverly combining, at distributing far, deep, and wide.

*Oh, how our modern eyes do roam – into the switchback structures of proteins that comprise our genes, through the galactic mist to Earth-like planets around distant stars. It’s gee-whiz-bang to the nth degree, intellectually fascinating, yet such far seeing isn’t likely to change our lives for a long time. Everything’s got to have a catch, no? For instance, scientists have developed a powerful new CT scanner that detects until-now-undetectable soft plaque in arteries – a marker of “silent heart disease” which afflicts apparently healthy individuals. Problem is, this magnificent magnification, this feat of coronary sleuthing, happens to be outrageously expensive and therefore cannot be employed to screen its intended audience – healthy, middle-aged folk like me – unless its price drops one-hundred fold. Of course, rich people can always pay out of pocket.*

*Be careful what you write about. A problem heart is just a short breath, a skipped beat away, and there I was last month in Mass General Hospital’s catheterization lab, twice, getting my atria examined by amazing gizmos at the tips of catheters inserted into veins in my arm and neck. Good news: no coronary heart disease or pulmonary hypertension. Not good: dilated right ventricle and pulmonary artery caused by a congenital abnormality called an atrial septal defect (ASD). A shunt, the doctors say. Translation: there’s a hole in my heart the size of a quarter, causing trouble over time. (Toss in anomalous pulmonary veins to further complicate matters.) Surgical consult pending. An ASD is a random glitch in the body’s system, over decades sabotaging the cathedral of the heart like a patient, artisan-vandal, and it’s not an inherited defect. So I can’t really blame my parents, and there’s no evidence that the anti-miscarriage drugs my mother took had a role, despite Internet med-gossip. Why, btw, did she go to such lengths to have a fifth, anomalous child? Why risk another miscarriage? Did my mom exercise control over her future, and by extension mine, or was it dictated by her husband, the censorious church or some primal urge beyond reckoning? I guess Leonard Cohen sang it best: “There is a crack, a crack in everything/that’s how the light gets in.”

@ @ @

(page 93) The poet Samuel Coleridge got it right: “The light that experience gives us is a lantern on the stern, which shines only on the waves behind us.” Or to quote the main character in Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel, Looking Backward, written in 1887 and set in a futuristic Boston of the year 2000: “One can look back a thousand years easier than forward fifty.”*

*Nonetheless, it’s hard not to try. I’m a big fan of Peter Turchin’s War and Peace and War, with its impassioned riffs on the life cycles of imperial nations, the meta-ethnic frontiers where empires arise, and the singular quality of asabiya – “the capacity of a social group for concerted, collective action,” – without which a country cannot survive. Uh oh – that’s us. I also admire Robert Jay Lofton’s book on the Aum Shinrikyo cult responsible for the 1995 sarin gas attacks in the Tokyo subway system. Lofton believes that Japan suffers from “psychohistorical dislocation – a breakdown of the social and institutional arrangements that ordinarily anchor human lives” a syndrome in which “people experience a profound gap between what they feel themselves to be and what a society or culture expects them to be.” Analysis not restricted to Japan – uh oh, again.*

*Indeed, looking ahead is almost impossible. Ray Bradbury, among the most esteemed sci-fi writers of the 20th century, had a talent for envisioning future scenarios replete with time travel, telepathy and advanced technologies, but he could not for the life of him envision a future in which women were not primarily housewives and a bit hysterical to boot. Female presidents, CEOs, doctors, lawyers, crime lords, TV anchors, geologists – unimaginable! And so his aproned honeys bake peach crumble on Mars while the men go out to laser-vaporize floating, blue indigenous life forms. Same as it always was.

@ @ @

(page 101) The clerk at Petsi Pies, who has that shaggy, perpetual grad student aura, notices the paperback in my pocket – The Elephant Vanishes, by Haruki Murakami – and we exchange enthusiasm for his work. I remark on a story in the book about a man who burns down old barns as a hobby and the grad student shakes his head, yes, yes, he knows it, but then the door chimes and a customer approaches the bakery case, pointing at a pie. The clerk and I nod at each other, co-conspirators in the vast Murakami cult.*

*Murakami’s books have sold tens of millions of copies and are translated into more than 40 languages. There is little exotic or Japanese about them, and with a few name and detail changes his stories could take place in almost any country in the world. He is a World Author writing World Literature. Kim Choon Me, professor at Korean University, says young people in South Korea “have found in Murakami a cultural code in which they can share their own conflicts and woes, a code that perfectly speaks to them.” She continues: “The more the world grows into a late capitalist society, his novels can be expected to spread with increasing force as transnational cultural commodities.” Not hard commodities, though, like Nike sneakers or McDonald’s hamburgers or Disney plastic action figures. Murakami provides commodities of dreams, elusive and beguiling dreams shared over bakery counters and across cities and oceans and barbed-wire borders. According to Roland Kelts, author of Japanamerica, readers see in Murakami’s narratives “the tones and colors of their own dreams…something they know and feel, but maybe cannot explain.” *

*Murakami-mania has only increased with record-breaking sales of his recent novels 1Q84 and Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and his Years of Pilgrimage. The obvious terminus of this trend, if Murakami can live and write long enough, is that every reader on the planet will one day buy a copy of his latest book, making him richer than Oprah. Murakami likens writing to eating fried oysters alone and lists Raymond Chandler and Kurt Vonnegut as key influences. Speaking of Vonnegut, I once heard him on the Imus in the Morning radio show say that Hitler should be sentenced in Hell to a never-ending orgasm, and that kind of lost me and Imus, too. Also, I must admire that phrase I coined in the footnote above, “commodities of dreams.” In the great commodities market for dreams, somewhere I think in Nebraska, would you be buying or selling?

@ @ @

(page 104) Over here, Draper Labs, the Whitehead Institute, Novartis. Over there, the Broad Institute, Genzyme, the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research rising from a fenced-off square of ground. The place is booming; it’s a little China, Dubai, Singapore, Bangalore. Here, in our backyard! Oh, what elixirs for longer and better life brew about me! What potions of hope immemorial! It cheers me that Elahna, a biomedical researcher as well as a pediatrician, is part of this grand effort.*

*She called during an earlier segment of this ramble and griped about the paperwork for flying eight genetically modified mice in from London. In New York they would undergo artificial insemination and then be mailed to her lab in Boston. You know, typical female yakkity-yak. The trials and tribulations of these mutant mice were funded with a tiny, tiny portion of President Obama’s $787 billion stimulus package intended to juice the U.S. economy. It’s all part of Elahna’s quixotic quest to locate the genes that cause kidney disease – kidney disease in mice, she will add in deprecation. One day she expressed discomfort for “wasting” taxpayers’ money on a project with low odds of success and I, the ever-helpful partner, reminded her that “negative results” (failures) can inform future researchers of which dead ends to avoid. So ship those mice already!*

* Alas, Elahna never published her negative results and soon left the basic research world to focus on clinical work, so some schmuck valedictorian genius may someday go down the same research rabbit holes. We keep repeating our mistakes, individually and as a species, although the saviors of big data, artificial intelligence, augmented reality and cross-departmental mindfulness promise to sort out the great garbage mound of information, both stupid and smart. Or things might just get mucked up worse, which might not be all bad. Perhaps my wife’s experiments bore ambiguous results (flopped) because her technician forgot to stir something clockwise rather than counter-clockwise and, therefore, with proper technique and the right glint of light through the 13th floor skylight, it’ll be Eureka! Eureka! the next time around.

@ @ @

(page 111) Tenants listed include Boston Paintball, an asset recovery firm, and a substance abuse counseling center. Are paintballers in there now, warless warriors ranging across a post-industrial landscape, pattered with red, blue, green, DayGlo orange, and security-stone pink?*

*Color, is that it? Is that what makes the world of today seem so different, so achingly modern, than the world of 50-75 years ago? The bright neon colors, the endless variations of shades, some of which do not under any circumstances appear in nature. A cavalcade of colors on hats, shoes, t-shirts, cars, city buses, and airplanes, crazy Calypso colors swirling on movie, PC, and cell phone screens, power colors streaking the donated clothes of the poorest slum kids. The past was so drab, the colors muted, isn’t that the idea? No cobalt blue on Cary Grant, no avocado green on Kate Hepburn.*

*Now I can add to that list the multicolored orange and lime-green sneakers everyone’s wearing. A variation on the modern-by-color effect, as described above, occurs in contemporary historical movies. For instance, I’d seen Jesse Owen’s feats at the 1936 Berlin Olympics only in black-and-white documentary form, but the recent film Race depicts his life and track-and-field victories in vibrant color. Who knew that U.S. athletes were issued blue boutonnieres upon arrival in Nazi Germany? The red of the swastika flags, like blood. In color, it seems as if it all happened yesterday. Semi-brilliant idea: add modern conveniences to films set in the past – swap guns for swords, iPhones for black rotary jobs, luminescent yellow Nikes for Jessie’s handmade Adi Dassler spikes – and time itself will be obliterated. Everything and everywhen will be now.

@ @ @

(page 121) So here’s the deal. Between early 2002, as the U.S. routed the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks, and late 2008, as voters chose a “Yes, We Can” president to deliver us from decline (ruined 401Ks, rusted bridges, eroded reputation, setbacks in Afghanistan, etc), over half of Americans changed their minds about the country’s prospects. Flip-flop: right to wrong. Silly me, for I had assumed that like the speed and heading of an ocean liner, the nation’s direction could not be so easily altered.*

*The inauguration of a new president buoyed the nation’s spirits, causing the wrong-track score to scud down to 48% by the spring of 2009, according to the NYT/CBS News poll. When the perceived bloom came off the Obama rose, the sense of national wrong-trackedness rose to 62% by the winter of 2010. Of course, these polls measure the pulse of Americans who can get to the phone before it stops ringing or whose hands can operate a cell phone without nuking the call. I mention this in deference to my aged, arthritic mother who complains, “I’ve never been polled!” She is personally affronted, suspicious of the entire enterprise. So I polled her myself: Mims, is the country on the right track? Of course not, she replied.*

*Since 2009, wrong-track ratings have fluctuated but never dipped below 50%; currently, in July of 2016, we sit at a disgruntled 76%. Right track: 18%. How, oh how, shall we reroute our national train? Resurrecting the 1950s, an era in which our over-rated prosperity depended on the misery of most everyone else on the planet, isn’t really an option. I say, stop consuming news about politics and crime and soon you’ll acquire a much sunnier outlook. Imbibing an all-day stream of negative imagery and confrontational rhetoric, not to mention ads for products you don’t really want or need and can’t afford besides, is not only injurious to self but not even representative of world trends. Of course someone is being killed, raped, mugged and discriminated against somewhere every second – we have 7.4 billion people out there and everyone’s taping everything! Of course politicians are corrupt and taffy-pull the truth – they’re politicians, for the sake of Richard M. Nixon! Enough! Remember the counterculture slogan “Turn on, tune in, drop out” from the 1960s? In 2016 it may be time for “turn off, tune out, drop in.” Turn off the pipeline of junk thought and hate that breeds dissatisfaction. Tune out the people transfixed by said circuses. And drop in to the world of neighbors, gardens and forest trails, of art and books, of homemade meals and conversations stuffed with stories, of backyard badminton tournaments, of tangible life. Btw, I haven’t succeed in doing these things, not far enough anyway, not yet.

@ @ @

(page 124) Since its debut, the Doomsday Clock has fluctuated between two minutes to midnight in 1953 to a comfortable 17 minutes at the end of the Cold War, in 1991. Alas, we slipped back to five minutes before the deadly stroke in 2007, but there are so many other alarming global developments that it’s hard to get worried or even notice anymore*